Andrew Lienhard: Blindfold Test

Welcome to a new Night and Day "Blindfold Test" with Houston pianist, keyboardist, and composer Andrew Lienhard.

(Andrew Lienhard; photo by Stephanie Lienhard.)

Welcome to the “Blindfold Test” for Night and Day with Houston pianist, keyboardist, and composer Andrew Lienhard.

Originated by Downbeat magazine, a “blindfold test” is a listening test that challenges the featured artist to identify and discuss the music and musicians performing on selected recordings. No information is given to the artist in advance of the test. I will be doing more of these for Night and Day, not only with jazz musicians, but with musicians from all genres, as well as artists and writers.

I don’t recall exactly how I met Andrew Lienhard. I believe we came across each other’s radar via Instagram, and from there, I discovered and became a fan of Lienhard’s original music, which is thoroughly steeped in modern jazz vernaculars and his classical piano training, but also embraces ambient, electronic, and trip-hop styles. His new album, Convolution, features Lienhard playing Rhodes, organ, and vintage and soft synths, with brilliant contributions from drummer Pat Williams and guitarist Mike Sunjka. The tracks pay homage to a few of Lienhard’s influences, including Pat Metheny and Houston legends, The Crusaders. One of my favorite tracks, “Five 13,” takes its name from the date of his mother’s birthday and has Lienhard playing some eerily beautiful Opus vocal samples over lovely piano and synth harmonies, and concluding, mysteriously, with the sound of gravel underfoot, and an idling freight train.

After graduating as a jazz major from the Houston School of Visual and Performing Arts (now Kinder High School for the Performing and Visual Arts), Lienhard attended the University of Houston, where he earned a Bachelor’s and Master’s of Science in Mathematics, and then the University of California, Berkeley, where he earned a Master’s of Science in Engineering. He is a very active member of Houston’s music scene and has played with several musicians I’ve written about and interviewed, including singers Kellye Gray and Horace Grigsby, both of whom are sadly no longer with us.

In this blindfold test, we discuss the range of music that has inspired him over the years, his parallel vocation as a software developer and engineer, and the challenge of playing really, really slow.

(Scroll down for a Spotify playlist of the following tracks.)

(George Duke; photo from georgedukemusic.com.)

George Duke

“Brazilian Love Affair” (from A Brazilian Love Affair, Epic, 1980) George Duke, vocals, synthesizers; full personnel is available here.

Long intro vamp here! (pause) Sounds like George Duke.

You got it!

I love him. He was this great keyboard player and composer, but he also had this falsetto singing that was really unique. One of my all-time favorite songs by him is “No Rhyme or Reason” from Snapshot . . . When I first moved to California, I spent a lot of time at Amoeba Music record store in Berkeley, and bought a lot of CDs, and that was one of them. The album just got under my skin, and I listened to that one song in particular a million times. It’s just a beautiful, heartfelt song. He’s always been very inspiring to me, because has this real melodic sense but he’s just so funky at the same time. Also, he’s got great sounds.

Were you gigging while going to school at UC Berkeley?

Yeah. Kellye Gray (singer), from Houston, moved out there the same time I did. So we were gigging together all the time out in the Bay Area. I spent a lot of my time playing when I should have been in school studying.

In the early to mid-90s, the Bay Area had all of these interesting cliques going on. Charlie Hunter (guitarist) was a part of it, and there was the acid jazz thing that was coming up. People were really into getting together and having sessions and just doing creative music. It was a really fun place to be a musician, and Kellye and I were really tight. She was a big part of my musical upbringing and a good friend for a time.

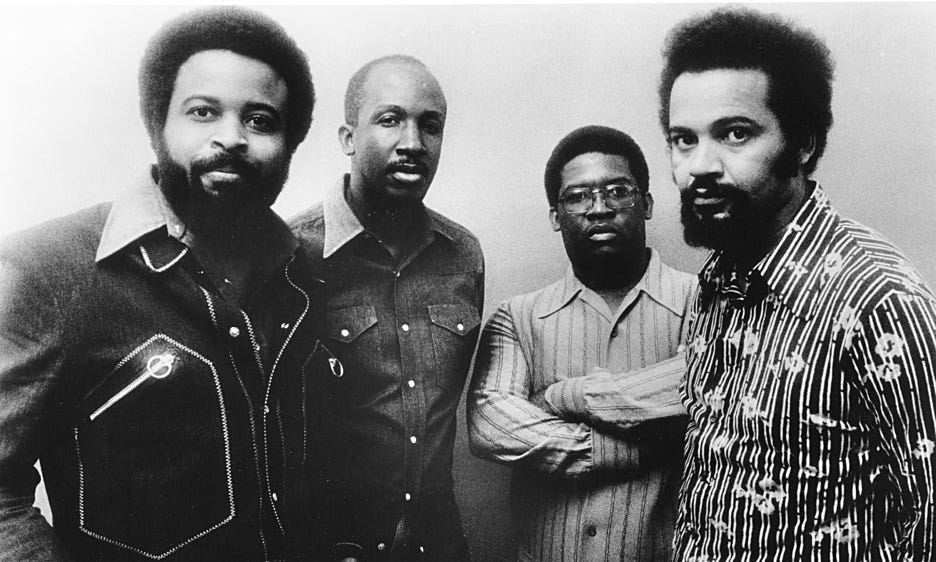

The Crusaders

“Stomp and Buck Dance” (from Southern Comfort, The Verve Music Group, 1974) Wayne Henderson, trombone; Wilton Felder, bass, saxophone; Joe Sample, keyboards; Stix Hooper, drums; Larry Carlton, guitar.

(Immediately) The Crusaders! Houston’s great band.

You play in a Crusaders tribute band?

Yes. The bass player Jelando Johnson has a band called The Crusaders Experience. Each month, we play the second Sunday at Emmit’s Place. The band includes Jelando, Andre Hayward, Joey Riggins, Felix Luna, Horace Alexander Young, and me. It’s just a fun, fun band. Sometimes the Sample family members come out. I love the music.

From the early 2000s to when he died, Joe Sample was around town. He would show up to your gig! So you’re playing Joe Sample’s music in front of Joe Sample. That was not an uncommon experience for a lot of us.

This has such a great groove. Speaking as a musician, how to you learn how to groove? Is it really just feel, or is there technique involved?

That’s a great question. The ultimate answer is you learn by playing with other musicians who have great feel. It’s hard to do it by yourself. But there’s also playing along with records, and certain metronome techniques. The best thing is to record yourself and listen back. Because the toughest critic is yourself. You’ll listen back and say, “No, that doesn’t sound good.”(laughs)

I kind of like the mentorship thing . . . There isn’t as much of that today as there used to be, when people would be really brutal to you, and tell you truth, you know? A great example of that was (Houston drummer) Sebastian Whittaker. A great drummer. He and I went to high school together, and he was brutal! Kellye Gray was the same way. They told you the truth, and that truth made you play so much better.

Do people get up and dance at your Crusaders gigs?

Yeah! For sure.

(Tricky performing in 2008; photo by Rama.)

Tricky

“Singing the Blues” (from Angels with Dirty Faces, Island, 1998) Martina Topley-Bird, vocals; Calvin Weston, drums; Tricky, keyboards.

(Immediately) I love this. Tricky. I love this album. I used to listen to this album so much when I was in New York. Did you see Tricky when he came to Warehouse Live?

No! But I remember you telling me a bit about that gig when I posted a photo of Tricky’s autobiography on my Instagram.

It was the most amazing thing. There were only about 75 people there! His band sounded like a freight train, they were incredible. Just that whole trip hop sound was overwhelmingly good. And at one point, Tricky just jumped off the stage and went around and hugged every single person in the audience. Before the show, he was just sitting at the bar, hanging out. No pretense at all.

That sound of the late 90s is really huge to me.

In an interview, Tricky once compared how he made music to finger painting. And you can hear it on this track, where there’s the drums and the looping sample, and it grooves, but it’s not locked in.

It’s that J Dilla thing where’s it’s not quantized, and there’s a looseness to it, but that looseness is still grooving. I bet he’d be great to work with.

(Tangerine Dream; photo by Monique Froese.)

Tangerine Dream

“Love on a Real Train” (from Risky Business, Virgin, 1983) Edgar Froese, keyboards, electronic equipment, guitar; Christopher Franke, synthesizers, electronic equipment, electronic percussion; Johannes Schmoelling, keyboards, electronic equipment.

Sounds like Vangelis. I’ve heard this before. I’m sure of it . . .

It’s music from a film. It accompanies a scene on a train.

That’s the Risky Business soundtrack. I thought Vangelis did that.

It’s Tangerine Dream.

Okay. They’re another interesting group. This is an iconic piece of music. It’s got this atmosphere but it also has this pulse under it, so it has rhythm! When you have rhythm and this atmosphere, people tend to turn their heads and listen.

I listen to a lot of atmospheric music as sort of “anti-music.” I don’t have to concentrate on it, but I want the emotional effect. Brian Eno’s albums Music for Airports and On Land were just huge for me. But I have friends who are like, “Why do you listen to this?” (laughs)

This track reminds me of Steve Reich’s music too.

Yes, you can hear the influence of minimalism.

I always thought that train song was Vangelis . . .

Emil von Sauer

(Emil von Sauer plays Chopin, Etude No.3. in E, op 10. 78 rpm recording shared to YouTube by 78.kenyszer.)

(Immediately) I know this piece very well! This piece is really easy for the first two pages . . .

Was the piano your first instrument?

My first instrument was violin. My mom was a symphony violinist. I grew up in Lexington, Kentucky, in a super classical music household. My dad sang in the Gilbert and Sullivan Music Society. I moved to Houston three weeks before I started HSPVA, and that was ninth grade.

So there was a lot of violin initially, but there was always a piano in the house, and I gravitated toward that. At some point, I just told my mom, I hate the violin, I’m never going to be a violinist.

But you loved music.

Absolutely. As a kid, I was really into piano playing singers. All of the 70s people you’d expect, like Elton John, Stevie Wonder . . . When Wonder’s album Songs in the Key of Life came out, I bought that record, and it just rocked my world. It was the greatest thing I’d ever heard in my life. I have three copies of that album on vinyl!

And you were learning to play classical music on the piano?

Yes. It was always classical. But I had this tendency to not want to practice the classical as much as I wanted to play tunes I was hearing on the radio.

There was no jazz exposure initially. But at HSPVA, everything changed for me. I was a classical piano major at HSPVA for two years, but by the time I was a junior, I was pulled fully into jazz, and graduated as a jazz major.

During this time, did you ever consider pursuing music a full-time career?

Coming out of high school, I had music scholarship things happening, but I didn’t want to do that for a variety of reasons. One of them is that I like doing things like math and computer science. I enjoy that STEM side of my world. I have been full-on as either one or the other, and for me, it never works. I have to have a balance. So I got a career in the computer world. Which is great for me, because I work here at home. I have huge flexibility to be a musician. I’m very happy with the balance I have in life.

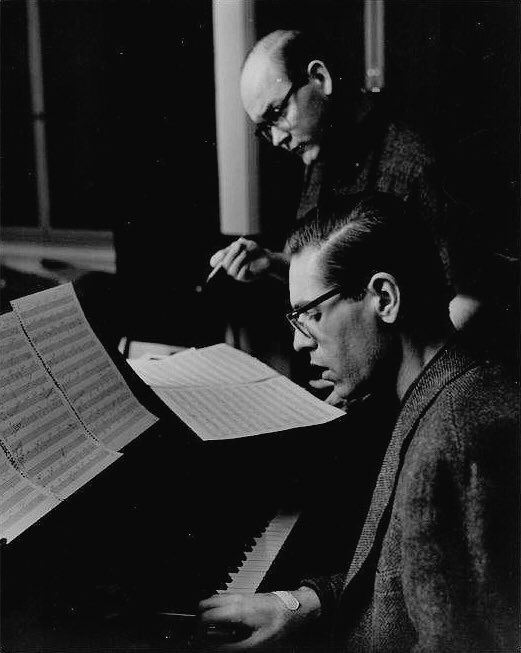

(Jim Hall and Bill Evans; photo by Steve Schapiro, 1962.)

Bill Evans and Jim Hall

“My Funny Valentine” (from Undercurrent, Blue Note Records, 1962) Bill Evans, piano; Jim Hall, guitar.

(Immediately) Ah, it’s Bill Evans. It’s a great album, with Jim Hall.

To my ears, and on this track in particular, neither musician is “accompanying” the other.

I had a long conversation with trumpeter Dennis Dotson about this particular version. We were doing a duo gig, and he said, “Let’s do ‘My Funny Valentine’ like that!’ Where nobody’s soloing, but everyone is supporting each other . . . and we worked on that, but I couldn’t do it. Not like this!

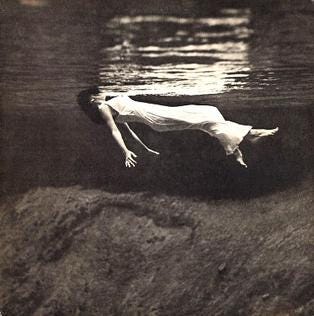

Jim Hall has such a warm sound, and he’s really melodic. He’s not underrated, but I feel like he should have been a bigger name. This album is one of the canonical duo albums. There’s another one they did together, but Undercurrent especially, with the cover of the woman underwater (see below) is what the music sounds like. Beautiful, suspended, but so masterful. The execution is so high. What Bill Evans is playing rhythmically is so sophisticated, and so precise, you know? It’s something to aspire to.

What are some challenges you run into as a pianist when playing with a guitarist, whose instrument is also a chordal instrument?

What is really comes down to is are you listening or not? You’re going to step on each other if you’re just plowing through, and not observing what they’re playing. But what happens, if you’re both listening, is you find this shared vocabulary of chord voicings, and you can play off of that. I did a lot of duets with Erich Avinger, a great guitar player, and we really enjoyed that sort of chordal interplay. When it goes south is when you have two people who aren’t aware of how it’s fitting together.

Some guitar and piano players will just lay out when the other plays, like if they’re in a quartet or a larger group. But I’d rather have both instruments comping, because it’s a conversation that just brings the music up.

(Shirley Horn; early publicity shot, 1960.)

Shirley Horn

“Blue in Green” (from I Remember Miles, Verve, 1998) Shirley Horn, piano, vocal; Ron Carter, bass guitar; Steve Williams, drums, percussion.)

(Immediately after the first chord) Ooo! Beautiful! It’s ‘Blue in Green.’ (pause) That tempo!

Mind if I just let this play? Because some things happen . . .

(After several minutes) Is this Shirley Horn? I love Shirley Horn. Only she could pull this (slow) tempo off. (Pauses to listen to Horn finally sing just one line: “Honey, from a horn. So sweet.”) There you go. The voice. That left hand comping that she’s doing, that’s Shirley Horn. Not a lot of people could play her music.

I saw her at Yoshi’s in the Bay Area, in a trio. I don’t remember the guys’ names . . . because they didn’t play with anybody else. They just played with her. Kind of like Nina Simone, Shirley Horn had a band. The thing about Shirley Horn is those tempos. She will play tempos that are just so slow. So how do you play that slow?

A non-musician might say, “Why is it difficult to play slow? Isn’t that easier than having to play fast?”

In a way, it requires more precision. Because the gap between beats is so large, there’s a lot of room for error when people play on the next beat. If they’re not subdividing, and feeling that tempo, they’ll never get there.

The other side of it is people want to rush, because it doesn’t feel natural to play that slow. Shirley Horn had so much patience, and that’s why her band was so good for her, because they were cool playing that slow! (laughs) Being able to play just three or four quarter notes at a really slow tempo is one thing, but to keep it there, even while you’re improvising, is super difficult.

And when the tempo is that slow, you don’t want to just hear the quarter note. You want to hear all of the stuff in-between, and all of the stuff in-between has to be in the grid, if you will, in the pocket.

Early on, that was one of the things that Kellye Gray would love to do. She would love to play the slowest blues on the planet followed by something just crazy fast.

I wanted to touch on Horace Grigsby, who you played with.

Oh, yeah. He was another singer who could sing slow.

David Craig (bassist) told me, if you heard Horace sing a song all by himself, without any accompaniment, you would feel the time and the pulse. Can you tell me a little bit about playing with Horace?

There was just a lot of fun with him. Horace enjoyed music so much, and he enjoyed listening to people playing with him. Horace would support his musicians so much and was so encouraging. His repertoire was enormous. And he could scat. Scatting is hard and can be very bad if it’s not done right. But Horace’s scatting was authentic. He just understood jazz so well.

When you first started playing with vocalists, was there a learning curve?

There was definitely a learning curve. I’m still working on that. Certainly, one of the great mentors I had in Houston was a singer named Anita Moore, who played with Duke Ellington. And again, tough love, real brutal, but so helpful. It was such an honor to play with her. Just a master musician.

I remember we were practicing a duo together, and Anita said to me, “Play more!” And I’m like, “What do you mean?” “Just everything! More!” (laughs)

Most singers would tell a pianist to play less!

Exactly. She wanted more support. It was one of those statements I had to think about for a long time. Not just arbitrarily “more,” but more more.

There’s this balance where you can over-voice and put too much density in the chords to where the singer can’t find their pitch. Pianists can become so enamored with chords to where they’re not supporting the singer.

I think it’s a really rewarding pairing, working with singers. I just love the texture and intimacy of it.

These are treasures my friend.

Great exchange. You really dug deep with a terrific player and a great guy.