Creative Arts Therapist Enrico Curreri

An interview with creative arts therapist Enrico Curreri.

(Photo by Yukon Haughton on Unsplash.)

Enrico Curreri, MA, is a Licensed Creative Arts Therapist at Elmhurst Hospital Center in New York City, where he works with patients ages 10-17 carrying different diagnoses, including major depressive disorder, autism spectrum disorder, PTSD, and childhood-onset schizophrenia. Whereas traditional psychotherapy, or “talk” therapy, is fundamentally a verbal experience, creative arts therapy utilizes different forms of the creative arts, either actively or receptively, as the primary means of communication and relationship-building with the patient, working towards shared goals.

In his practice, Curreri, who studied music composition at the New England Conservatory of Music, embraces all of the arts. In individual and group therapy sessions, he has introduced patients to contemporary and avant-garde composers, including Luigi Nono, John Cage, and Frank Zappa, as well as the repertoire of such transgressive musicians as Lou Reed and David Bowie. He has also utilized the “cut-up” writings of William Burroughs, art by Jean Michel-Basquiat, and scenes from the HBO series, The Sopranos.

Zappa is a recurring presence on Curreri’s Creative Arts Therapy YouTube channel, which features several educational and entertaining videos about Creative Arts Therapy, as well as his young patients’ reactions to specific songs played during group projective writing sessions. There’s also a series of videos titled Burning Away, which showcase the transformative ritual of burning a patient’s artworks, at their request, as a ceremony for emotional release and healing.

This is an interview I’ve been talking about for a while, and I appreciate everyone’s patience while I transcribed, edited, and collaborated with Enrico to ensure what you read here is accurate and engaging!

What is creative arts therapy?

The answer that people would probably give you -- and then I’ll give you mine -- is that a creative arts therapist is a mental health professional, a psychotherapist who uses the creative arts, like art, dance, drama, music, and poetry as therapeutic tools to help patients explore their emotions, improve their mental health, and enhance overall well-being.

My version of it is, I use art forms to get to know, discover, and experience patients and how they function in the world on a daily basis. I use the arts as a way to understand them. And on a deep level, I think all creative arts therapists would agree we’re using different art forms as a means for discovery.

You discover things about your patient or patients, and then find ways where art can be therapeutic, and help them with things like behavioral issues, or dealing with past trauma?

Yes. Some therapists might just want to look at the behaviors, while others might want to focus on past traumas and history. I like to develop an intimate, or what we call “spacious intimacy,” with the patient or patients, and look at how we are connecting together in the moment. That’s really what I’m mostly concerned about. Not really past experiences, but more what’s going on with our therapeutic relationship in the moment, and if there are any hang-ups that the patient or even I might have and explore what’s going on with that.

If a patient comes in and they’re shaking their leg constantly, we can look at that and ask, “What’s going on there?” Art is a less tense way of exploring too much leg shaking or lack of eye contact. If stuff from the past comes up, we can explore that. But I’m more concerned about affective engagement in the moment.

When you arrive for work at the acute psychiatric unit, what happens? What does your job entail?

The day begins with psychiatric rounds. We’ll discuss the patients, though not in detail. As we go over each patient, anybody may bring up something they think is important, maybe something that happened over the weekend, and we can all chime in. After rounds, we have group therapy sessions — maybe three groups a day, sometimes four — and in the middle of that, we’ll see individuals. Throughout the week, there are staff meetings, supervisor meetings, and supervision by the supervisor. There are also community meetings, and hanging out with the patients to talk about different issues on the unit. Even when they’re eating, I might go out and hang out with them, or go to the school on the unit, and see how they’re acting in the classroom.

There’s also supervision with new creative arts therapists, going toward licensure. I’ll meet with some of them, they’ll tell me about their cases, and we talk shop! (laughs) It’s great to see new creative arts therapists and how excited they are about the profession and the work they do.

What brings a patient to the psychiatric care unit?

A tween, teen, child, or adolescent is brought to the emergency room when they are in a mental health crisis posing an immediate danger to themselves or others or experiencing severe emotional distress that requires immediate intervention. Some examples of situations requiring emergency care include suicidal thoughts or behaviors; homicidal thoughts, threats, or behaviors; drug overdose or substance abuse crisis; psychotic episodes with severe hallucinations; inability to provide basic care for oneself; and any major unsafe shifts in behaviors. Those are the basics.

In the emergency room, the ER staff will conduct an assessment to determine the nature and severity of the crisis. If necessary, medication may be administered to stabilize the patient. If they’re going to be discharged from the emergency room, the ER staff will make referrals to the appropriate mental health staff professionals or facilities for ongoing care.

If the patient needs to come up to us, if they’re deemed to be high risk, they may be admitted to the inpatient psychiatric unit for further evaluation and treatment. It’s supposed to be acute, short-term care, maybe lasting seven to ten days, but sometimes they’re in there for three weeks. Special needs patients might be there for six months to a year. It’s case by case. More rarely, a patient might be there for a few days before the parents want them out.

(Photo by Basit Abdul on Unsplash.)

The patient population you treat is very diverse.

I believe the hospital where I work has over 100 interpreters and translators. Our zip code was identified by National Geographic as one of the most ethnically diverse zip codes in the United States. I know that a lot of psychology interns compete to work here at this location because they want that experience, with all of these diverse religions and cultures. The neighborhood is so diverse. It’s nice!

Within certain ethnic communities, there is a lot of stigma about mental health. Is this something you encounter, where a parent or guardian just doesn’t understand what is happening with a young patient?

Yes. Within some religions, including the Abrahamic and Eastern religions, the patient’s parents won’t understand (what’s happening), and believe, “Just pray, and it will go away.” Or it’s the karma that’s causing this to happen.

One side note that’s really not entertained at the hospital, and I was just speaking about this to my fellow creative arts therapists, in some cultures, if someone is preoccupied with out-of-body or religious experiences, and it’s getting to a point where it’s consuming them, here (at the hospital), they want to work with that with medication. But they don’t consider that in some cultures, that person might be chosen by the community to become a shaman.

What is the difference between psychosis and a colossal religious experience? These things are not really entertained at work, but I think the younger generation of doctors is more interested in this. There’s a whole practice of what we call transpersonal psychology, where it’s mind, body, soul, spirit. They look at the spiritual side, and ask, Is this patient going through some kind of religious experience, and are the drugs stifling that? They might need to get through this, and it will pass. Some professional psychologists have had these types of colossal religious experiences when they were young, and they didn’t overmedicate themselves. They went through it. They journaled or did paintings and got better.

Carl Jung’s The Red Book is an example of what you’re describing.

Yes!

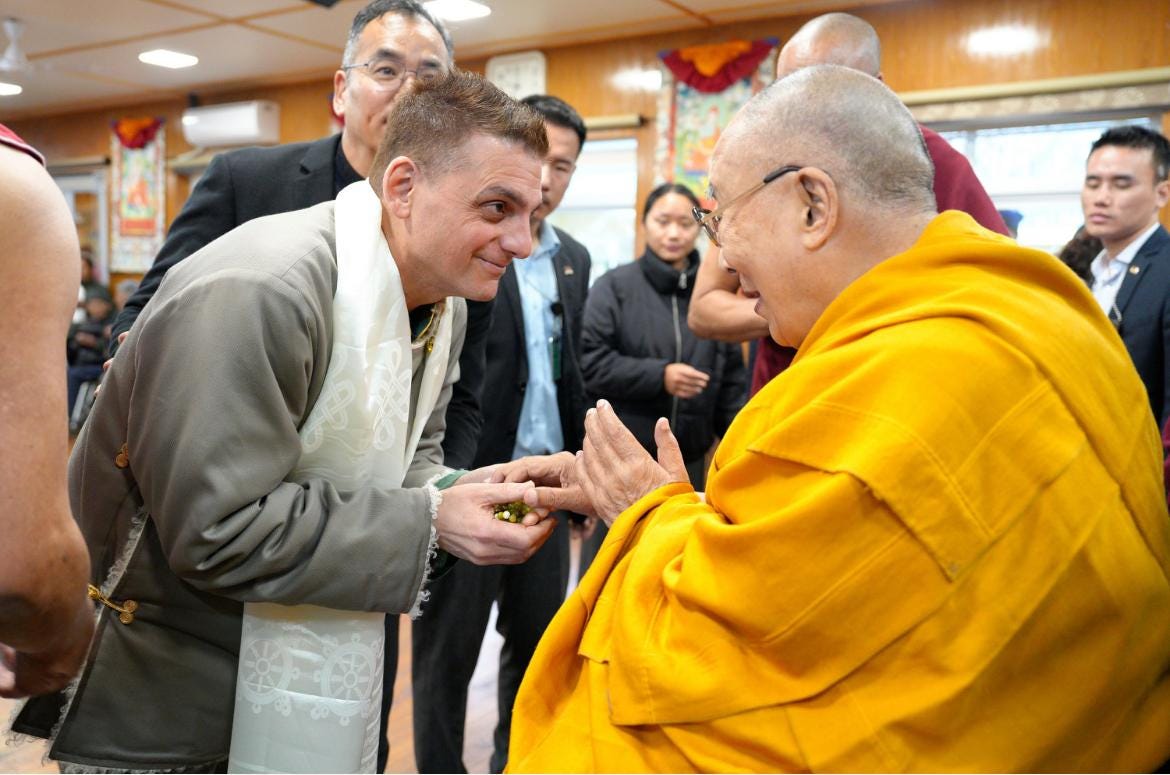

(Enrico Curreri and the Dalai Lama, 2025.)

You studied music composition at the New England Conservatory of music?

Yes. I graduated from NEC with a Bachelor of Music in Composition.

I was a horrible high school student. I wasn’t going to go to college, but I was studying guitar and composition privately with a teacher. At my mother’s urging, I went to Nassau Community College, where I studied classical guitar. I got really interested in composition after hearing Aaron Copland’s Piano Variations, and listening to Stravinsky, which woke me up to Frank Zappa’s classical side. I got into NEC as a composition major.

That’s impressive! When you get a degree in composition, typically, you go on to teach other people who are pursuing a degree in composition. But you decided to do something very different.

Before I began studying to become a music therapist, I was at Boosey and Hawkes, while trying to make it as a composer and a singer-songwriter. Right after graduation, I was sending compositions out, and while writing parts out, I would sometimes listen to WBAI and stations like that, and I heard these holistic doctors talking about sound and music therapy. That’s when I started to get the spark. My mother gave me articles about sound healing and suggested I study music therapy.

Meanwhile, I wasn’t getting my pieces performed, and eventually, I got fired from Boosey and Hawkes. But I needed to get out there. They gave me a nice severance, and then I went and auditioned and got into the music therapy program at New York University and dedicated my life to creative arts therapy.

Having known you for a while and learing more about the work you do as a Creative Arts Therapist, I know you have a gift for connecting with a population that others might feel very uncomfortable around. In addition to your musical gifts, that is a gift as well.

When it comes to working as a therapist with patients who you might call misfits or outsiders, there are two figures who influenced me: Andy Warhol and Frank Zappa. Those two really focused on hanging out with the people who were thrown to the side -- outsiders or misfits. I think Warhol’s people are a little closer to the patients I work with, because a lot of them can be over the top. Especially with patients who are diagnosed with oppositional defiance disorder, where they’re just always trying to challenge authority

(Creative arts therapist Enrico Curreri.)

How would you describe your Creative Arts Therapy YouTube channel?

It’s a channel for the therapeutic community, including therapists of all types, and doctors in medicine and psychiatry. But it’s also for fans of the art forms and the artists that I’m speaking about. The original idea (with the channel) was to bring those fans along with the patients, therapists, and doctors, and create this online therapeutic community.

There are a lot of competing ideas of what a “therapeutic community” is, but I think, at a basic, in-person level, it’s about strategically placing therapeutic peers in the patient’s daily life. The therapeutic community extends beyond traditional settings like hospitals and mental health facilities to include such outpatient environments as a psychiatrist’s office, other multi-disciplinary psychotherapy practices, health food stores, bookstores, restaurants, libraries, and mental health clubhouses. My idea was to include online spaces. So, a YouTube channel can now be a helpful resource for the patient.

Social media gets a justifiably bad rap when it comes to mental health. It can be used for good, but it’s often used to create unnecessary stressors, bullying, and abuse. But your channel is helpful to someone like me who wants to learn more about Creative Arts Therapy and watch videos that describe the therapy in action. I’ve also shared videos from the channel with artists and musicians I’ve written about.

You may be one of the first arts writers to include the clinical arts in your coverage.

You describe yourself as a Buddhist, correct?

Yeah, but also looking at Jesus as a Buddhist and a prophet. If you break it down, I’m a Buddhist monotheist, to which a lot of Buddhists would say, “What’s that about?” Because a lot of Buddhists go on the atheist side. I think being in the West, and being brought up in the Abrahamic religions, the creator and monotheism are always there, and don’t conflict with the Buddhist teachings at all. You ask Tibetans, and they couldn’t care less if someone believes in the creator or not. They’ll say, “Oh, I hope there is one.”

You have a series of videos on your channel where you burn artwork by patients who have requested you to do so. Does this connect to Buddhism?

I think it extends from a Buddhist practice. Burning away from negative energies. It’s a ceremony and a ritual, but it’s also a drama and Creative Arts Therapy. I love that idea in drama therapy that you’re creating these rituals and having a whole ceremony as the therapy.

One of your videos, We're Only in It for the Healing: Zappa in the Therapy Room!, features The Mothers of Invention, where you use the album, We’re Only In It For The Money, to create different kinds of creative arts therapy experiences for your patients. What compelled you to select this particular record?

I think because of how it segues from one song to another. It has a flow to it. It jumps from different types of sound collages to songs. One of the goals was just to turn the patients on to this type of experience. Sometimes, the patients are stuck eating the same fast food, listening to the same five songs, doing the same thing every day, and they don’t try to explore anything new.

Before I decided to play the album in its entirety, I had included the song “Mom & Dad” in some mixes of music for group sessions. The patients always found that song to be “creepy,” but they related a lot to the lyrics.

Which is really interesting, because with all of the drill rap they’re listening to . . . It’s funny, because when I play Lou Reed and Frank Zappa, the patients will do a double-take when they hear the lyrics. They’re like, “Wow. I didn’t expect that to come out of the song!” But they’re listening to so much harsh music!

We assume young people can’t sit still, but your patients were mesmerized by the album.

They also had a visual art form with them: a big roll of paper on the floor and oil pastels, pens, and paints to use. They engaged in projective drawing and painting while the music was playing.

Do they get instructions from you, or can they just draw whatever they want to draw?

The instructions are not what to draw. The instructions are not to talk, that we’ll talk when the experience is over, and don’t stop until all the music is finished. If you need to take a break, you can stop and meditate on what you drew, but don’t start saying, “This sucks!” or “This is great!” If you love (the music) or hate it, draw what that looks like. There’s no right or wrong, appropriate or inappropriate. This is not a drawing lesson.

Did your patients connect with the lyrics, and what Frank Zappa is singing about in these songs?

Those lyrics are pretty clear, so they catch that. But a lot of it is the one sound experience going into another, and then another.

Like a collage.

That catches them, and they’re absorbed in that, like, “What the hell’s going on? What’s going to happen next?” and it helps with the flow of the drawing experience.

With the child patients, when they listened to this music, they just started laughing! But then, some of them would look at me, making sure it was okay to laugh.

Your instructions are not to talk, but laughter is okay.

Yes! Because I’m laughing too!

And that’s one positive outcome of this experience that you took note of, that patients are laughing and realizing it’s okay and healthy to laugh.

Another thing was that the substance abuse patients thought the album had to be a drug-induced creation and found out Zappa was drug-free. That’s what the mind can do when you’re really creative. You don’t need substances to get there. And the album acts as a kind of drug-induced experience.

This links back to finding your own path, making sure it’s spicy, doing your own thing, and the importance of taking creative risks.

You mention “racing thoughts” in the video, which is something patients with attention deficit disorder experience. How did the Zappa album help those patients?

It matches what they’re experiencing. The Zappa record keeps changing, which helps them focus on the drawing. It keeps them focused and occupied.

When you selected this album, did you anticipate these results we’re talking about?

No! I think I put it on just to turn them on. (laughs) They were the right patients at the right time.

Which goes back to what you were saying about being in the moment with your patients and being ready to bring something new into the therapy room.

As I said, there are quite a few patients who are stuck, eating the same the fast food, listening to the same five songs. They might be bullied. They’re just stuck. And there’s no one to talk about the arts with! So why not give them something to catapult them into an interesting experience? It’s a Buddhist thing! To wake them up and stimulate the mind!

🙏🏾❤️

Thank you for this interview!