Dan Sumner: Blindfold Test

Welcome to a new "Blindfold Test" for Night and Day with guitarist Dan Sumner.

(Dan Sumner; photographer unknown.)

Welcome to a new “Blindfold Test” for Night and Day with guitarist, music producer, and educator Dan Sumner.

Originated by Downbeat magazine, a “blindfold test” is a listening test that challenges the featured artist to identify and discuss the music and musicians performing on selected recordings. No information is given to the artist in advance of the test.

Based in Monroe, Louisiana, guitarist, music producer, and educator Dan Sumner has traversed a long and winding path that on paper may seem overwhelming. But, in conversation, and in the following “blindfold test,” Sumner eloquently draws connections between the breadth and depth of his musical and cultural experiences, including 13 years living, performing, and teaching in New Orleans before Hurricane Katrina uprooted him and his family. (As a former New Orleans resident, it means a lot for me to begin the following “test” with music from and a conversation about the Crescent City.)

Born in Indianapolis, Sumner experienced a deep connection to music and the guitar at a very young age, and went on to attend Capital University in Columbus, Ohio, where he studied and became close friends with guitarist and composer Stan Smith. After graduating, Sumner received a scholarship to study at the New England Conservatory in Boston, where he earned a master’s degree in jazz studies. His instructors at NEC included such luminaries as guitarist Mick Goodrick, composer George Russell, and drummer and percussionist Bob Moses. Sumner now holds a doctoral degree in Music Education from Indiana University’s Jacobs School of Music, and has held faculty positions at several colleges and universities, including Loyola and Tulane University (New Orleans), and the University of Louisiana (Monroe). He has toured worldwide with several acts, including Permagrin, a duo project with drummer Louis Romanos that explored the potential of jazz, rock, and live looping technology.

Currently, Sumner plays guitar in Doug Duffey and BADD, featuring singer, pianist, and inductee of the National Blues Hall of Fame and the Louisiana Music Hall of Fame, Doug Duffey. The band’s August 2025 album, Souvenirs, was recorded and mixed by Sumner at his Fort Sumner Studio. Sumner’s other recent projects include transcribing, in notation and tablature, several rare vintage recordings of Mississippi-born jazz guitarist Snoozer Quinn (1907-1949), including performances recorded in 1949, when Quinn was hospitalized at New Orleans Charity Hospital for tuberculosis. Those transcriptions are published in Snoozer Quinn: Fingerstyle Jazz Guitar Pioneer. Dan is also a sponsored Benedetto artist and plays a bespoke 16-B archtop jazz guitar, handmade by master craftsman Bob Benedetto.

I met Dan when I was a composition major at Capital University, so we go way, way back (We laughed a lot throughout this “blindfold test.”), and it is a true pleasure to introduce Night and Day readers to his inexhaustible enthusiasm for music and life.

Enough. As they say in New Orleans, “Le bon temps roule!”

(Scroll down for a Spotify playlist of the following tracks.)

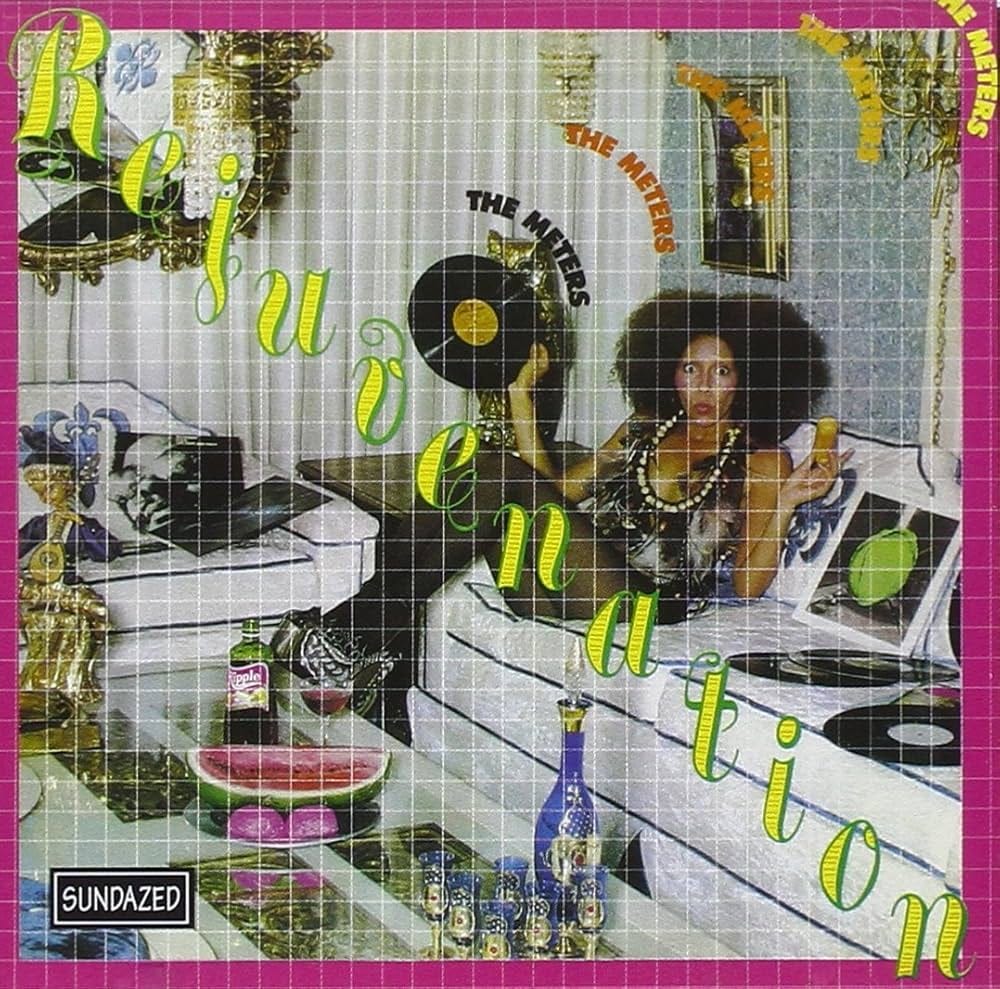

The Meters

“Just Kissed My Baby” by The Meters (from Rejuvenation, 1974, Reprise) Leo Nocentelli, guitar, background vocals; Art Neville, keyboards, vocals; George Porter Jr., bass, background vocals; Ziggy Modeliste, drums, vocals; Lowell George, slide guitar on “Just Kissed My Baby.”)

It’s The Meters with “Just Kissed My Baby.” Deep, deep stuff! Really fundamental.

Had you heard The Meters before you moved to New Orleans?

That’s a great question. I don’t really know. My guess is yes, but nobody ever pointed out that that’s The Meters.

I can tell you from the first few notes of hearing The Meters’ recordings, I felt it right at the pit of my soul. It just resonated. New Orleans resonates. You lived there, you know what it’s like. It resonates on a lot of frequencies, right? Some of the best frequencies that I’ve ever felt! And then there’s the polar opposite, both sides of the fundamental.

It’s a city of extremes.

It’s a city full of bon vivants who are happy to be alive. I have a deep connection to the city. It’s even deeper now than when I lived there.

After you arrived in New Orleans, what are some things you had to learn on your instrument to play something like “Just Kissed My Baby” convincingly?

This is a clichéd way of putting it, but it is in the rhythm. New Orleans has a certain vibration to it that doesn’t exist anywhere else I’ve been, and it takes a while of being there to reset your internal rhythm. I had to go from a frontal lobe-centered approach to music to a visceral approach. One doesn’t negate the other, but each balances the other.

When I lived in New Orleans, I felt like I was the least New Orleans player in the town. (laughs) New Orleans was initially hostile when I moved there. I didn’t get any gigs. I was just finding my place. I did some teaching; we had a couple of kids, and then Katrina happened. We were displaced and ended up in Bloomington, Indiana, and stayed with my parents until we realized we couldn’t go back anytime soon. So, I go from being the least New Orleans player in New Orleans, to the most New Orleans guy in Indiana! (laughs). Next thing you know, I’m playing New Orleans stuff all the time.

While you were displaced, did you miss and appreciate New Orleans and its music even more?

Yes. More than I can express.

Eventually, you and your family were able to relocate from Bloomington and settle in Monroe, Louisiana, where you met Doug Duffey. When did you two meet?

In 2015. I was playing a gig in Monroe with Jeremy Davis and the Fabulous Equinox Orchestra, which is kind of a super high-end wedding band out of Savannah, Georgia. All pros. At the rehearsal, we ran through two pieces we were going to do with a special guest (Doug Duffey). Afterwards, backstage, getting ready for the show, I heard a pianist out there playing and singing. I was like, “Who is this guy? He’s great!” I stick my head out, and it’s Doug. We get onstage, do our thing, and when it comes time for Doug, he comes out, and the crowd goes bonkers, like Mick or Bowie just walked onstage. We did two songs with Doug: “On Your Way Down” by Allen Toussaint and Doug’s “New Orleans Rain,” which is probably his most famous song. During “On Your Way Down,” this really slow grind of New Orleans funk, when it was just me and the rhythm section playing, Doug turned all the way around to see who was playing guitar. We made eye contact, and after the show, talked and agreed we were meant to work together.

Snoozer Quinn

(Snoozer Quinn; image from silent film footage c. 1932.)

“Snoozer’s Telephone Blues” by Snoozer Quinn (from The Magic of Snoozer Quinn, recorded 1949 and 1953, released 2014, 504 Records), Snoozer Quinn, Guitar.

(Immediately) This is Snoozer Quinn! (listening) Did you hear that F minor 13? That’s like a Ravel chord.

I hear it! Did you transcribe these recordings for the book Snoozer Quinn: Fingerstyle Jazz Guitar Pioneer?

Yes. Kathryn Hobgood Ray is Snoozer Quinn’s great-grandniece, and there was always talk in the family about him. When she went to do her master’s thesis in musicology at Tulane, she got approval to write about her grand uncle. Steve Howell decided to publish Snoozer’s biography with transcriptions of Quinn’s 1948 and 1949 recordings.

The project was like doctoral dissertation work, because no one had ever done this before. No one had ever gone back and looked at this one thing that had happened: In 1949, Snoozer was in Charity Hospital, and his friend Johnny Wiggs visited with an acetate recorder. He set it up in a nurse’s station, dragged a microphone over, handed Snoozer a guitar, and said, “Go.” And Snoozer just sat there and played.

Why was Snoozer in the hospital?

Tuberculosis brought on by acute alcoholism.

When you listen to the recordings, you notice some interesting things happening. Snoozer didn’t work in what today we could call “open” tunings, but he would take just one string and drop it, and that took me a while to figure out! (laughs) I would get to a spot in the music, and there would be a chord or passage that would be physically impossible to play on the guitar, and I would have to do a little CSI work and figure it out.

It was an amazing year-and-a-half experience of sitting here and digging through history. As part of the book tour, we went to New Orleans to the Jazz Museum, and Katy brought out Snoozer’s guitar, the guitar he played on those 1948 recordings. I got to play it, and it was a very interesting headspace to be in, a vibrational thing, you know, to play his music on his guitar.

(Andy Summers and Robert Fripp; image credit: DGM/Panegyric)

Andy Summers and Robert Fripp

“I Advance Masked” by Andy Summers and Robert Fripp (from I Advance Masked, 1982, A&M), Andy Summers, electric guitars, Moog and Roland synthesizers, piano, Roland guitar synthesizer, Fender bass, percussion; Robert Fripp, electric guitars, Moog and Roland synthesizers, Roland guitar synthesizer, Fender bass, percussion.

(Immediately) I figured one of these (tracks) would show up! I love these albums. Turn it up!

This music, to me, always made me think about riding one of those Tron motorcycles through the Bonneville Salt Flats and trying to get more and more out of the thing. (laughs) You can also imagine Bowie coming in at any point! Or Daryl Hall of a certain period.

This track, for the uninitiated, is from two instrumental rock records recorded by guitarists Andy Summers of The Police and Robert Fripp of King Crimson. These albums had an impact on you and your playing, right?

When I first started playing guitar, for real, it coincided with the rise of The Police into public consciousness. Andy Summers’ sound is the thing that got me, although I identified more with Lindsey Buckingham’s sound, which is more roots-centered. But to hear a guitar that sounded like Andy Summers, or a guitar like Fripp’s that sounds like a thousand digital typewriters, just banging away, had a profound impact on me.

But it wasn’t just the sound that drew me in; it was the underlying ethos of it, the story and attitude of it, and the strength of the statement. And the confidence, whether ginned up or real (laughs), to throw it into the ring and say, “Yeah, this doesn’t sound like Led Zeppelin. This doesn’t sound like middle-of-the-road songwriting. This is a little bit different.” That’s what has drawn me to a lot of different types of music.

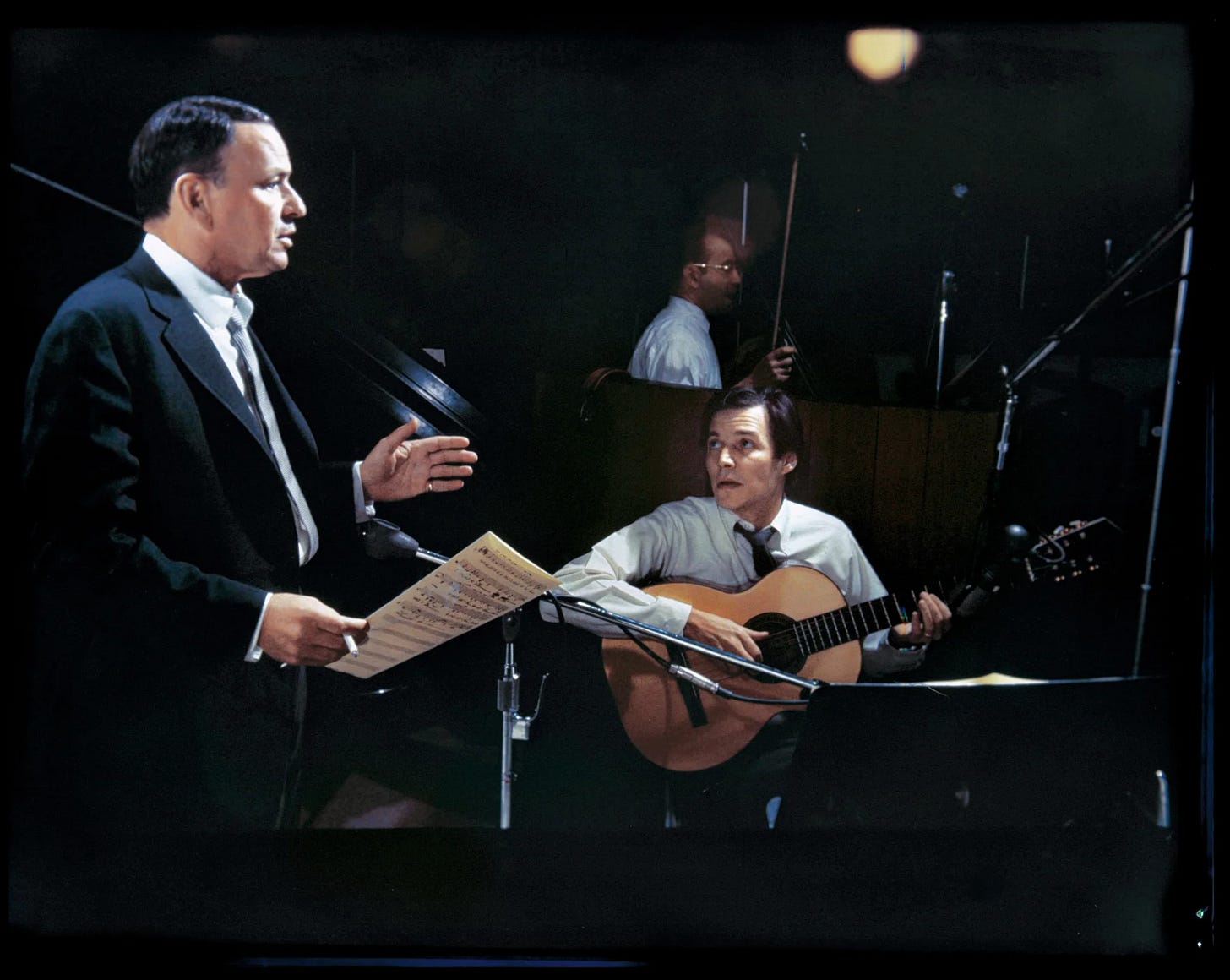

(Frank Sinatra and Antônio Carlos Jobim; courtesy of Frank Sinatra Enterprises.)

Frank Sinatra and Antônio Carlos Jobim

“The Girl from Ipanema” by Frank Sinatra and Antônio Carlos Jobim (from Francis Albert Sinatra & Antonio Carlos Jobim, 1967, Reprise), Frank Sinatra, vocals: Antônio Carlos Jobim, piano, acoustic guitar, vocals; Claus Ogerman, arranger, conductor.

(Immediately) I’m going to sing the trombone line!

1962. Sinatra and Jobim. “The Girl from Ipanema.” Really, the definitive recording of that song. Arrangements by Claus Ogerman. Bossa nova has been very important to me as a musician, guitarist, and co-writer.

Jobim’s playing is so beautiful. Talk to me about bossa nova. One can recognize a bossa nova immediately, but why is that? Are there rules to this music? Is there a template, a clave?

Jobim was a songwriter in the traditional sense of the term. He wrote songs about shit that mattered to him, evidenced by Passarim, which is a whole album about deforestation in Brazil. Beautiful songs about horrible things. And that’s a good way of thinking about the blues, and what music can do. But to break it down, this music is centered around the bossa nova clave. We’re in four-four, and here’s the clave . . .

Listen to Dan Sumner explains the bossa nova clave:

They do this in Cuban music in the bass, and what it does is propel the music forward. You get this loping thing that happens. It’s slow-moving, but it’s moving. And because of that really strong accent on the and-of-three, and then the and-of-four, you get a double punch. And then you have the songs of Jobim, which are beautiful, on top of that.

(Bill Frisell; photo by Monica Frisell.)

Bill Frisell

“The Beach” by Bill Frisell (from In Line, 1982, ECM), Bill Frisell, guitar; Arild Andersen, bass.)

(Listening intently) Is this off of Bowie’s Low?

Nope.

That’s Fripp for sure . . .

It’s not!

Is it David Torn?

You’re in the ballpark!

It’s not Frisell.

Yes, it is! This is from Frisell’s first album for ECM, In Line. This track is kind of an anomaly on the album, which is mostly solo.

It’s great. Total Frippertronics! (laughs)

I think I first encountered Frisell’s music around 1986. His sound caught me; it was like a guitar on hallucinogens, with impossible and deeply expressive tones. I was also drawn to his use of, or rather, insistence on using dissonance as a thickening agent. “The Days of Wine and Roses” from Is That You? is an example. A bit of pointy steel added to drive home the meaning behind a pretty melody. And his re-imagining of rock and roll on the opener of Where in the World? (“Unsung Heroes”) is so heavy.

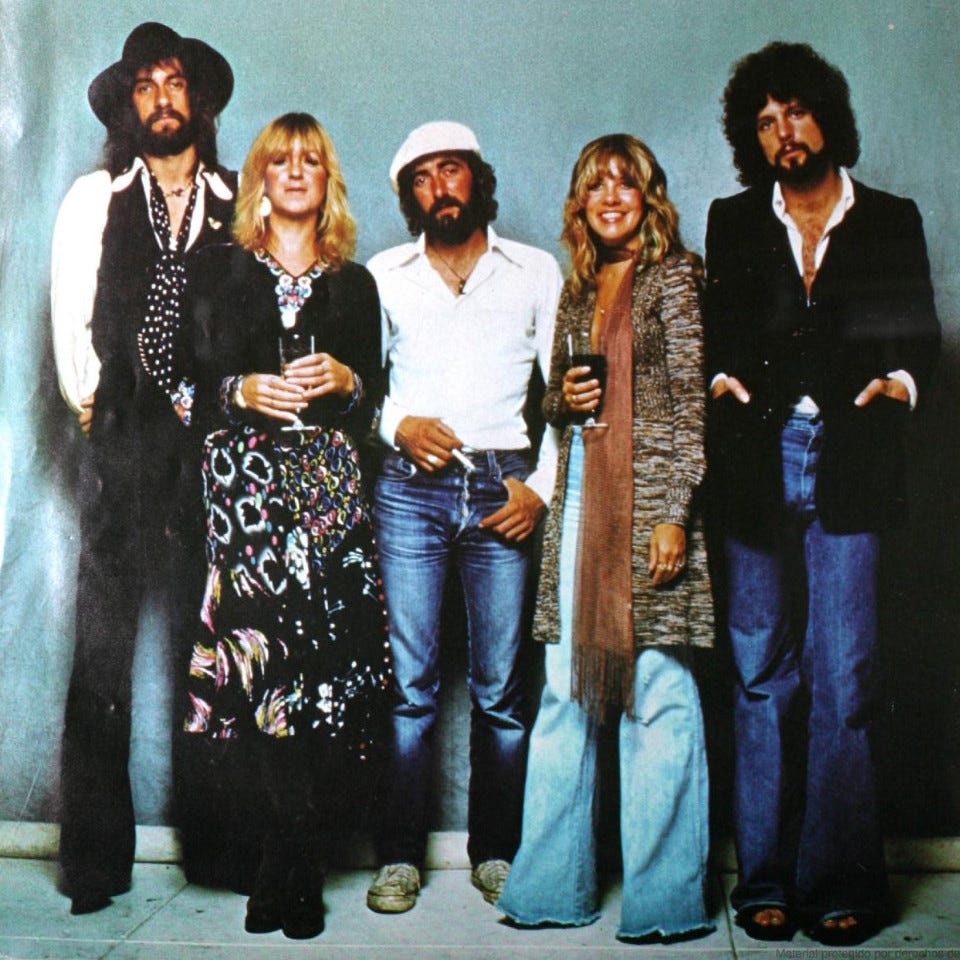

(Fleetwood Mac in 1977.)

Fleetwood Mac

“Dreams” by Fleetwood Mac (from Rumours, 1977, Warner Bros.), Lindsey Buckingham, vocals, guitars, percussion; Stevie Nicks, vocals; Christine McVie, vocals, keyboards, synthesizer, vibraphone; John McVie, bass guitar; Mick Fleetwood, drums, percussion.

(laughs) Yeah, man! One of my earliest musical memories is hearing this album. I was on a plane, and I heard (sings) “Don’t stop thinking about tomorrow . . .” It was on rotation on the earbuds. I was about nine years old, and it was so compelling.

I chose this track for two reasons. I wanted to hear you talk about Lindsey Buckingham, and the kids’ band you lead, The Melters (formerly, The Face Melters). This is a tune you had your young musicians play, correct?

Yes. My kid band program at Fort Sumner Music School is different than School of Rock in the sense that I really try hard to focus on a couple of things. If the kids are really listening, then whatever music they’re into, I’m going to go with them. But I also focus on teaching the things that I know. I go to the things I know are great and give them the ice cream right at the beginning. I get them playing, let them feel it, and then point that out: “Did you feel that? We had it, right there!”

The trumpeter Wynton Marsalis said he learned how to swing from (drummer and band leader) Art Blakey, who put his swing underneath what Wynton was playing. That’s what I try and do. I have them give me enough where we can hold something steady, and then I’ll throw the groove, the rock, funk, or techno underneath it, and see who it lights up.

This is what (drummer, percussionist) Bob Moses did for us when I was at the New England Conservatory of Music. He would throw his groove underneath us and see what happened. That has never left me. That is the way you teach.

Lindsey was the first guitar player I heard who I heard myself in, and I’m not sure why. I wasn’t playing guitar at the time, but I latched onto his voice.

Do you mean his singing voice?

No, no. His “voice” on the guitar, the notes, the rhythms . . . The way he played the guitar resonated with me in the sense that it sounded like I was the one playing the guitar. That’s what I used to imagine as a kid, and I still do today, to try and draw some of what moves me into my own playing.

And then you have Lindsey’s solo records. I think the first time I engaged with anything that you might call avant-garde was when I heard Go Insane, with “D.W. Suite.” You get to the end of side one, and there’s a locked groove, like musique concrete. That’s going insane, right? (laughs)

One of the things I do as a producer, or when I’m writing with Doug. When we get to the end of a song, and it’s kind of cooking along like a Fleetwood Mac track, I’ll say, “Okay, I’m going to put an outro solo on this!” like Lindsey would do! (laughs) Like on “Love Into My Life” from the Louisiana Soul Revival album. And on that track, I told Doug, “We have to fade it.” Because it’s gotta go on forever.

"[A]city full of bon vivants who are happy to be alive."