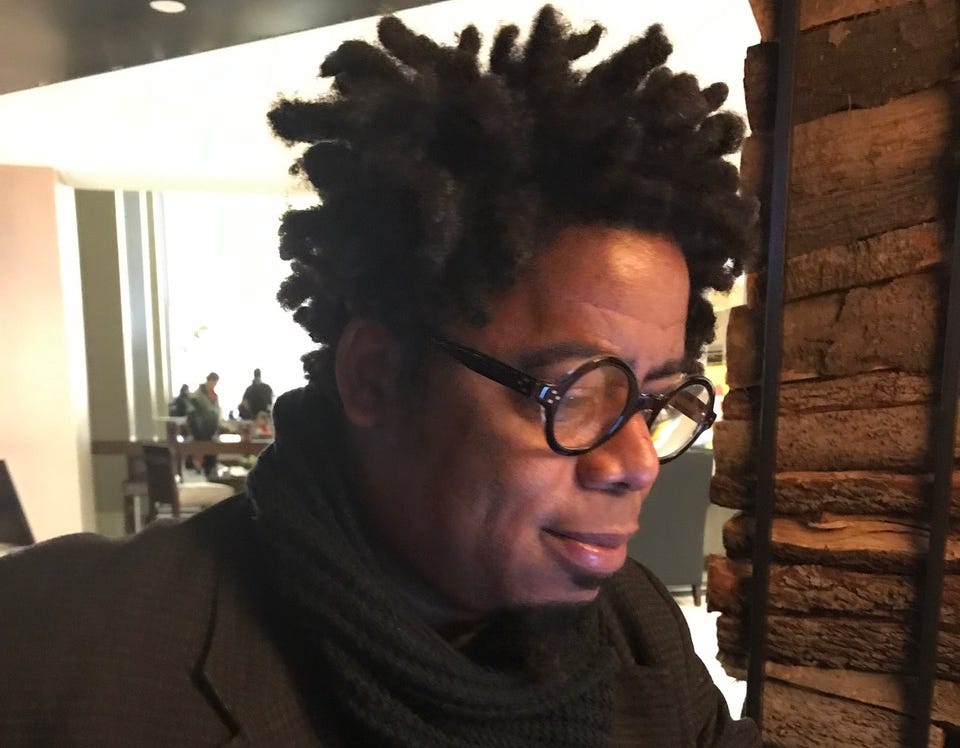

David McGee

A conversation with Houston-based visual artist David McGee.

(David McGee; photo by Tara Conley.)

Houston artist David McGee and I met through our mutual friend Tierney Malone, a painter, jazz historian, and DJ, and one of the first friends I made after relocating to Houston in 2010. David and I got to know each other by sharing links, images, and YouTube videos of music we enjoyed via social media before meeting in person at his East End art studio, a former Vietnamese beauty shop. Inside what McGee described as “a sacred space,” several canvases were turned to face the walls, and a decorated Christmas tree still stood even though it was, if memory serves, the first month of spring. I brought a beat-up recording of Erik Satie’s Socrate for voices and orchestra, put it on the turntable to play, and proceeded to converse with David at great length about jazz, art, and the sociopolitical climate of the times. (One of Tierney’s paintings hung in the room where we sat.) David and I have continued that conversation ever since. One of the joys of an enduring friendship with an artist or musician is witnessing the development of their work over time and finding inspiration in their bravery and willingness to maintain a steady practice, dig deep, and remain vulnerable.

Born in 1962 in Lockhart, Louisiana, David grew up in Detroit, Michigan, and moved back to the South in the 1980s. He received his BFA from Prairie View A&M University in 1985 and had his first solo exhibition in 1986 at Houston’s legendary Barnes-Blackman Galleries. Since then, David has shown in several prestigious institutions across Texas and the country, including The Menil Collection, Contemporary Arts Museum Houston, Houston Museum of African American Culture, and The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. As a master of both figurative and so-called “abstract” painting (we discuss that troublesome word in this interview), David’s work is infused with scrambled, surreal references to literature, art history, American politics, film, and popular culture, and resonates with the love and fear that comes with being alive. It’s also gorgeous to look at and is among good company at Inman Gallery, where his 2023 exhibit, The Tarot Cards and The Gloria Paintings, featured some of his most timely and deeply personal works to date. In October, his dramatic, large-scale watercolor and pencil series, Avenging Angels, was featured in the 36th edition of The Art Show at the Park Avenue Armory. And it has just been announced that David is a recipient of a 2024 Louis Comfort Tiffany Foundation Biennial Award. (The competition grants $20,000 awards to artists selected for their talent and individual artistic strength.) Looking ahead, his debut institutional survey, David McGee: The Griot and the Nightingale, will open March 14, 2026, at the Bechtler Museum of Modern Art (Charlotte, NC), organized by Katia Zavistovski, the curator of modern and contemporary art.

For this interview, David and I spoke in a quiet corner on the second floor of the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston’s Nancy and Rich Kinder Building. We commandeered a couch hidden behind Joseph Havel’s bronze sculpture Domestic Flag (before stars), which sits next to Dorothy Hood’s 1969 oil on canvas painting Haiti, a breakthrough work Hood described as “the difference between a small orchestra and a full symphony.” What follows is an extension of our first dialogue on a beat-up couch in his former studio, perhaps more formal but now informed by a longstanding friendship.

Some people might not be aware of the physical demands that painting requires. Like playing an instrument, it can be hard on the body, especially as we get older.

I think sometimes the medium preps the emotional state that you’re going to find yourself in. Oil painting allows more freedom to improvise in ways that you wouldn’t do in other mediums. Painting with water-based paints is a different kind of anxiety because they dry differently. But with oil, you can improvise over the surface, and your body is much looser, because you know there are second and third chances, based on the drying time.

Watercolor is my primary focus right now. But when people call me a “watercolor painter,” it’s not true. That’s just the thing I’m focused on now. I’m just in that mode. I’m in a literary mode, and for some reason, watercolor is best suited for that mode. But it causes a slowing down which physically is a little irritating because your body is tight. Your hand stiffens up, and your body stiffens up. You know you can’t erase. Each mark is the mark. It’s like fresco painting; each mark is the thing. And if, like me, you don’t use the color white, and instead use the white of the paper, it’s like printing, where you have to remember where the highlights are going to be, which makes everything labor intensive. If you’re doing drapery, and there are lights and a shimmering in the drapery, well, you have to remember (quietly) don’t touch this thing.

Doing four- or five-hour sessions like this, your breathing changes.

And not in a good way!

Right! It’s very physical, especially if you’re doing it on a larger scale. So I have to get ready for that.

Do you begin with sketches before you go in with the watercolors?

No. I write in notebooks that describe how I want everything to feel.

So it’s not a visual description?

It’s a literary description. Even if it’s an image based on one of the Old Masters, the image I am painting has nothing to do with the originator’s intent. I’m not interested in that intent. That intent is not informative for me, because that was his time. I’m interested in the same way Charlie Parker was interested in Stravinsky.

There’s a great story about Charlie Parker calling Charles Mingus and saying, “Listen to this,” and then putting the phone down, and improvising over a recording of Stravinsky’s Firebird Suite.

I’m interested in overtones, and the feeling of the thing, but not the interior complications, because there’s no way to get into that.

What do you mean by “the interior complications”?

Basically, the emotional weight of the subject, or that subject’s or the painter’s state of mind.

The question for me is, how do I borrow that feeling, that form, and inject my analysis into that image? Well, I have to write that down, so I can read it to myself out loud. A friend of mine told me, the best way to deal with poetry is to read it out loud. But when you look at my sketchbooks, you aren’t going to see any drawings of my paintings.

And no drawings of birds?

No, no, no. A woman in New York City told me (while looking at one of my paintings), “I’ve never seen a hummingbird that big.” I said, “Of course you haven’t!” (laughs) There’s no such thing as a hummingbird or a butterfly that big. These are metaphors, this is a painting. So, I’m not interested in getting the wings “right.” I’m interested in the form.

(David McGee, Nutcracker, 2024, watercolor on Arches 300lb cold press watercolor paper.)

You mentioned drapery, and I was reminded of my conversation with New Orleans artist Jacqueline Bishop about the influence of draping as it is used in fashion design in her paintings.

My interest in drapery is based on Velázquez. He could paint drapery so beautifully, and so realistically, but when you got closer, they look like little abstract touches. I found that you can manipulate the viewer by not doing much! I love that in watercolor. They look a certain way from a distance, but when you get close to them, they’re almost abstractions, with hundreds, thousands of little marks.

People like Alexander McQueen, Jean Paul Gaultier, and all of those French couture people are very, very useful to me. But the main thing is staging and theater. I love theater and opera, where people are posing, but they’re not! (laughs) They stay still to say something, while all of this stuff is happening around them.

That’s how I would describe the women in the Avenging Angels series. You’re not painting from models, right?

Right. The faces come from my imagination. The problem with that is, their looks are going to be the subject matter, how their facial expressions convey clues to the painting, you know? Which is a hard thing to pull off. I don’t want them to look too histrionic, I don’t want them to look too dramatic, but I want that interior complexity. You don’t know what they’re thinking, but you know they’re plotting.

You wonder, “What is she thinking?” You kind of know, but you can’t articulate it. So you look at the objects they’re holding, the insects and birds around them, the lighting and drapery, and the painting’s title.

There’s a painting of mine we recently showed in New York City titled Nutcracker. In that painting, in the facial expression of the woman, I did want to show madness. She’s looking off in space, like she is a little “off.” She’s on the verge of doing something, but you don’t know what she’s going to do. She can no longer be wounded by anybody’s actions. She’s made her mind up. But in order to get to this place, you have to be mad, and her face shows it. No matter what happens around her, the subject is in the cosmetics of her face.

You don’t work from photographs, correct?

For the faces, no. There are a lot of watercolors I’ve made, like the Ready Made Africans series, where I did have models. But I couldn’t find the faces, so I had to direct people how to look. I would make drawings (sketches) before painting because I couldn’t tell them to stand still for ten hours.

They weren’t professional models?

No, no. I don’t like “professional” people. I like regular people who have no clue about any of this stuff.

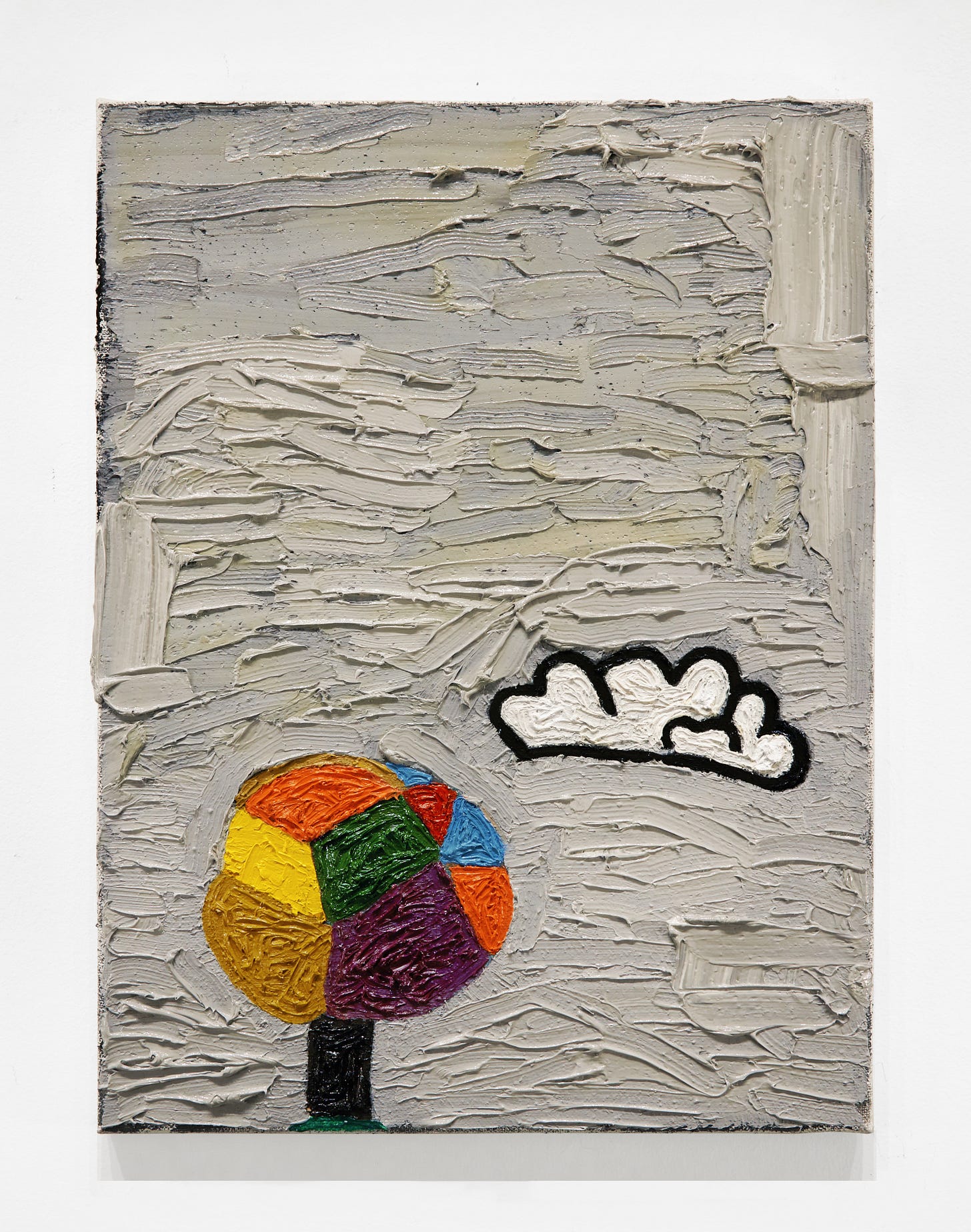

(David McGee, Tree and Cloud, 2021, oil on burlap.)

I want to talk about The Gloria Paintings. I’m not sure if I would describe them as “abstract.” I feel that’s a word arts writers lean on a little bit too much. But do they connect back to the lineage of abstract art?

The Gloria Paintings are not abstract. They are figurative, but they use abstract language. They seem like shapes you’ve seen before, including satirical, comedic shapes from nature. The so-called abstract paintings that came before, the Urban Dread series and The Complications of Water, are pure abstract language.

But the Urban Dread paintings do remind me of concrete urban things, like a fence, a window, or a police car, even though, at first glance, you might not see that. Only rarely in The Complications of Water paintings would you include a legible word or something that looked like a little creature. The visual and painterly language was abstract, but very grounded in the imagery in Moby Dick and I think touched on what we all had experienced as a city in the wake of Hurricane Harvey.

I don’t know if anything is truly “abstract.” I would never call myself an abstract painter; I just think certain images demand a certain way of painting them. I would never want to do “figurative work” of Moby Dick. I would just lose my mind with boredom.

There’s a performative aspect to abstract painting, like with Jackson Pollock, where it’s easy to connect the painting with the action of painting it. So the work is described, maybe not inaccurately, as if the painting was a performance, and the artist was “angry” or in a state of whatever while creating the work.

But, looking at the Complications of Water paintings, I don’t get the sense that you were out of your mind throwing paint on the canvas . . .

Oh, no, no, no.

But you went somewhere to create those paintings. You traveled to another place, literally, to work, specifically, a shed surrounded by dirty water.

It’s my dirty romance! I was in a mental state too. I couldn’t afford to go to all of these exotic places, so I needed to go somewhere isolated and harsh, where you couldn’t listen to any media, and there was nothing to do for months on end but to do this thing.

You wanted to lean into it.

Right. Plus, it took me a long time to read Moby Dick. It’s beautiful, but it’s a piece of work! There’s something about what happened on the Pequod that continuously happens to our society, this fake-ass democracy. On the Pequod, there’s a mania, and there’s a witness to the mania. When I got through it, I thought, I have to do something with this.

Then I started connecting water with the Middle Passage, and a different kind of obsession and mania, and how water engaged barely curious people in this intense space. I could feel, physically feel, how enslaved Africans felt in the bowels of those ships. I was also researching J.M.W. Turner’s painting The Slave Ship, and what that was all about.

When I made those paintings, there was no mad sloshing around, just really focused mark-making. For me, everything is like a mark, step back, a mark, step back.

I think you’re a very strong person to go there and be open to feeling the trauma of the Middle Passage. You hear this from people of Jewish ethnicity, who have never been in a concentration camp, but they know what that feels like. Armenians talk about this too, the heritage of trauma in one’s DNA. A lot of other folks might not have been able to feel that and then produce a work of art.

Silence is pretty hardcore. That’s why the pandemic bothered a lot of people. They don’t want to sit with these feelings, and instead engage to a point of distraction.

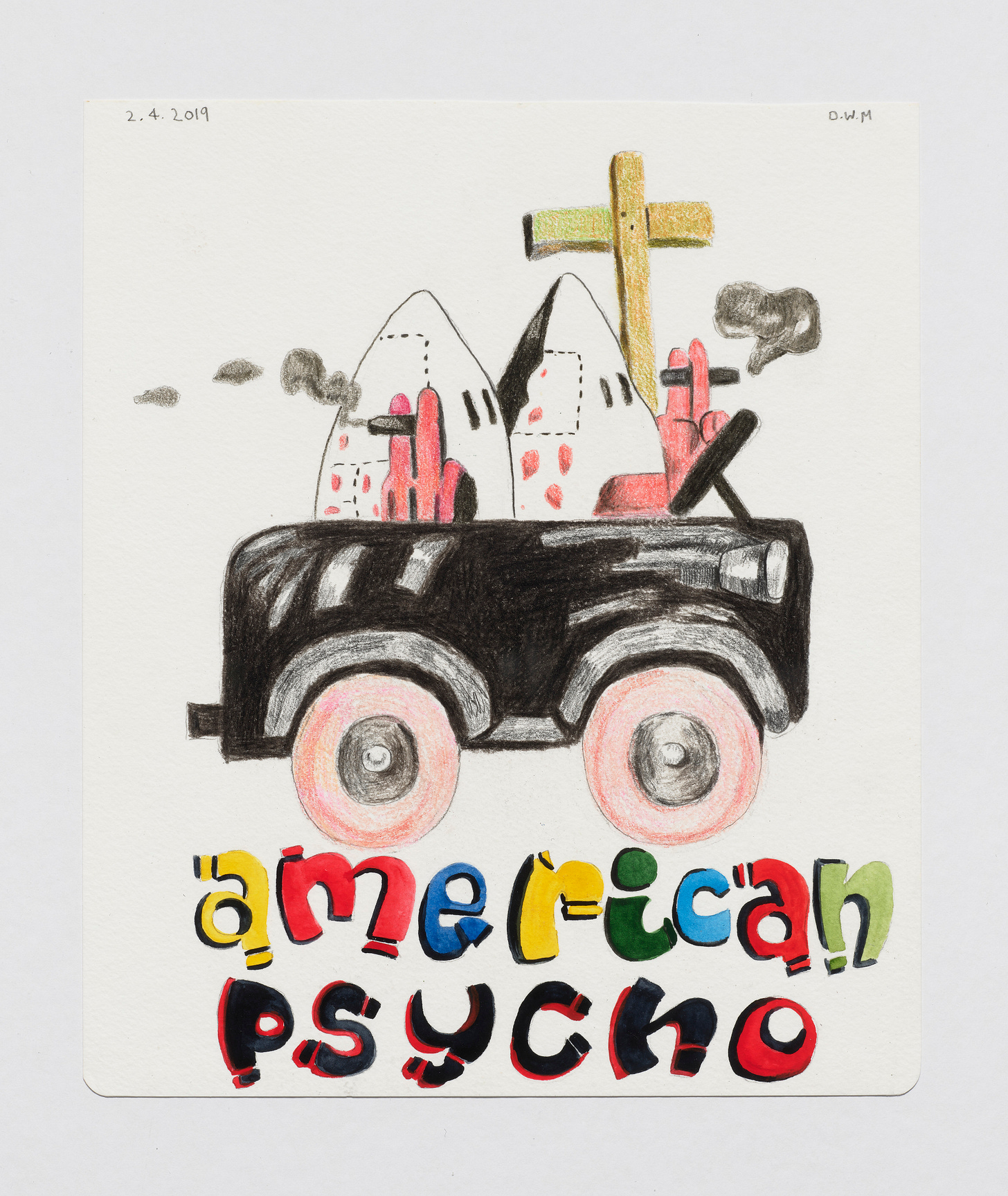

(David McGee, american psycho, 2019, graphite, colored pencil, and gouache on paper)

We’re still reeling and recovering from the pandemic. The aftermath of that time, and the Black Lives Matter protests, compared to where we’re at right now, is overwhelming. Many leaders in that movement are no longer with us. They’re dead from suicide, so-called natural causes, or have been killed. And now, we have a very violent president and administration in place.

Is art one way to navigate all of this? How do you negotiate this mania?

I don’t think any creative person can escape the zeitgeist of the moment. I don’t want to fault youth, but when you get older, you know how to nuance experiences of the culture. When you’re young, you’re so open to and reactive to things, whereas when you’re older, you learn how to sit before you react. You have all of these things you remember and recall and can nuance things other people might not understand or “get.” You don’t have to be current with the times. That’s why you don’t see Bob Dylan making comments about today’s world, and when he does, it’s in that little masterpiece about JFK, “A Murder Most Foul.” If you listen to that entire song, he revisits all of this.

First of all, regarding the election, I misread the culture so badly that my feelings are hurt.

I think a lot of us did. What that campaign tapped into, is the very thing we were talking about earlier, about Complications of Water and Urban Dreads. It had nothing to do with the price of eggs or working-class Americans unhappy with the economy. And the misogyny was over the top.

I’ve never seen a country so dependent on the power and contributions of women and have such a loathing for them on the down low.

You talked about how, as we get older, you are able to sit before you respond. You have this wellspring of inspiration, life experience, perspective, etc. That’s a blessed thing, to be alive and have all of that, and to be alive in the first place!

Right and to realize all of that.

At our age, a lot of men go in the opposite direction. They close down. They become very frightened, and think, “No! They’re coming to get me!” and that’s how you get a Trump in office.

It’s an ignorant mania.

Another thing, Chris, that helped me though, is my mother Gloria’s illness. It really put me on solid ground. I was wavering a little bit before that. I have to admit, before I made some career decisions, I was kind of in a “raft of Medusa,” surfing on a board. I didn’t really know what was happening with me. But nothing can stabilize you like serious illness, and when Gloria was diagnosed with cancer in 2020, I woke the hell up and realized it’s not all about me. It changed my outlook on how I should engage with everything outside of art. But art is everything too because I work throughout. I made The Gloria Paintings while my mom was going through chemo, but I can’t remember making one.

You made a lot of work during that time.

I started The Tarot Cards and The Gloria Paintings. I would wake up at four in the morning to give her shots, and I would just make those tarot cards. At first, I didn’t know what they were about. I had no clue until 30 or 40 in. Once I figured that out, I thought they were a little dark, and said to myself, “Well, I need to make something for Gloria.” Especially after she rang the bell for the first time. (When you finish your chemo, they ask patients to ring a bell, and it’s so moving.) But I didn’t know how to do it. Then one day, I was listening to Charlie Parker With Strings, and saw an image of a Pierre Bonnard painting, and decided modernism was the way to pay homage (to Gloria. A certain kind of modernism from the 1920s and 1950s, when you could talk about serious stuff, but there was a way of celebrating it, almost like an MGM film in technicolor.

The first time your mother saw The Gloria Paintings was when they were exhibited at Inman Gallery. You didn’t show them to her each time you finished one.

It was a bouquet to be shared with her later. In them, you can see the power of art and the power of the human spirit when it’s not trying to paint for an audience. The best art is made without audience approval. You’re just doing it to maintain sanity. Even if it’s a gift for somebody, it’s still for you. She saw the paintings, and they did what they were supposed to do.

You can work on automatic pilot, not knowing what the hell is happening. Through grief and uncertainty, you can do your work. That’s not fucking romantic either! That’s the deal.

A true pleasure talking with my great friend Chris Becker, I have a deep appreciation for the work he's doing in spreading the word on the importance of creativity and it's engagement.

Love David!!