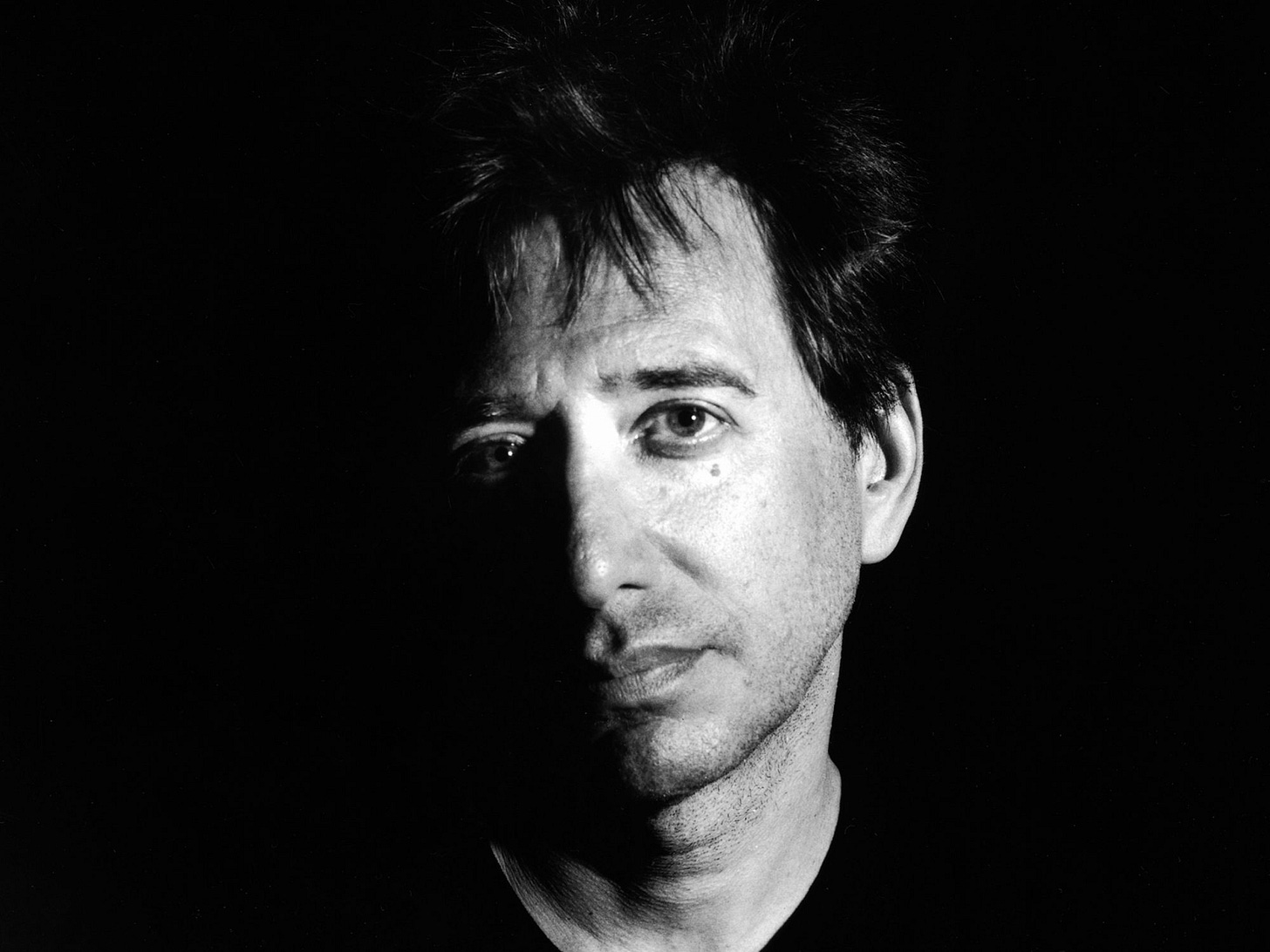

John Pickford Richards of JACK Quartet

An interview with JACK Quartet violist John Pickford Richards about playing the music of John Zorn.

(JACK Quartet, photo by Shervin Lainez)

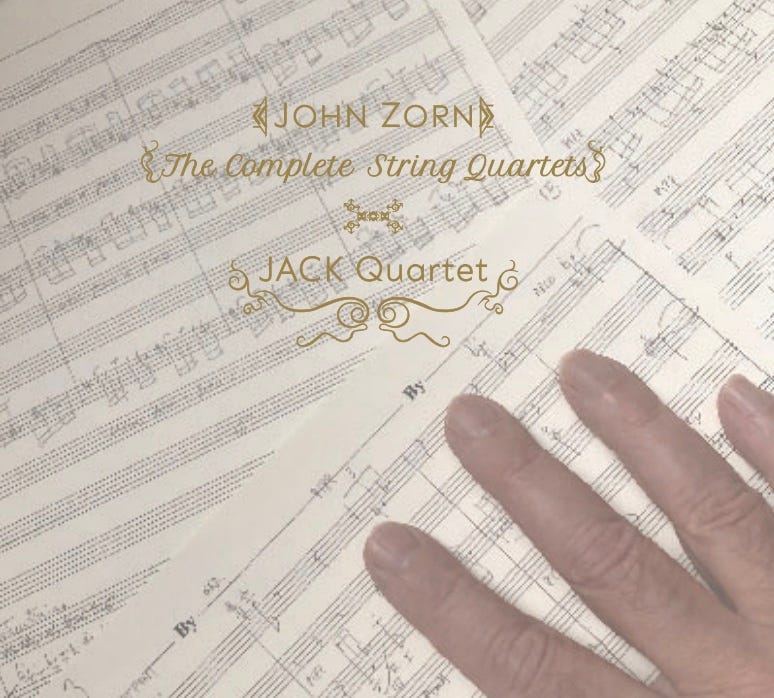

In the liner notes of his 1987 album Spillane, composer John Zorn wrote, “Whether we like it or not, the era of the composer as autonomous musical mind has just about come to an end.” But haven’t composers always relied on the auspices of and friendships with great musicians. A natural collaborator, Zorn, 71, has always worked closely with and benefited from what was at first a small, and over the years has grown into an expansive network of creative, virtuosic musicians from the worlds of free improvisation, metal, jazz in all of its guises, and classical music. Among his many close collaborators in the classical world are the GRAMMY®-nominated JACK Quartet, who on Jan. 19 will release the first-ever recording of Zorn’s complete string quartets, including two works, The Remedy of Fortune (2015) and The Unseen (2017), composed specifically for JACK. Founded in 2005 by violinists Christopher Otto and Austin Wulliman, violist John Pickford Richards, and cellist Jay Campbell, JACK enjoys longstanding relationships with many contemporary composers and maintains a prolific commissioning and recording catalog. On Friday, Jan. 17, JACK celebrates the album’s release with a performance at Roulette Intermedium of Zorn’s Necronomicon (2003) and Memento Mori (1992) with special guest Ikue Mori.

My first encounter with Zorn’s music was his 1986 album The Big Gundown, a wide-ranging and wholly original tribute to the great film composer Ennio Morricone. (Originally released on Nonesuch, The Big Gundown was rereleased in an expanded edition on Zorn’s independent label, Tzadik.) The fearlessness in how Zorn simply ignored the delineation between composition, arranging, and orchestration and drew inspiration from musical genres and styles that exist well outside the walls of academia had a profound impact on me. Later, while in my first year as a theory and composition major at Capital University’s Conservatory of Music, I heard Kronos Quartet perform in concert Zorn’s 1988 composition Cat O’ Nine Tails (Tex Avery Directs the Marquis De Sade) on a program that included works by Charles Mingus, Arvo Pärt, and Jimi Hendrix. Something was in the air. That kind of programming, and certainly Zorn’s aesthetic, was very unusual for the time.

Years later, it was a real pleasure for me to interview JACK violist John Pickford Richards about working with and playing the music of one of my favorite composers.

Do you recall the first time you heard a piece of music by John Zorn?

The first time I remember becoming really aware of John Zorn was at an old Bang on a Can marathon when Ethel quartet played Cat O’ Nine Tails. I was sitting very close, and they were just really on fire with it, and I just thought it was the coolest thing I’d ever heard. I think I had heard Forbidden Fruit already, but I hadn’t processed who John Zorn was. Cat O’ Nine Tails really stuck with me, and shortly after that Bang on a Can performance is when JACK programmed it ourselves.

What struck you about Cat O’ Nine Tails (Tex Avery Directs the Marquis De Sade)? Did it sound different than anything you’d heard previously, or did it harken back to some music and composers you were familiar with?

It was definitely in the “channel-switching” category of Zorn’s music, where the styles just change on a dime without any set-up or transition, and that really spoke to me, because my own musical tastes are kind of all over the place. Having all of those different styles in one piece made sense to me, and the way they all spoke to each other was so musical. It also gave the quartet, the actual players, the opportunity to really play. I was attracted to that.

When you say, “really play,” are you talking about where there’s no traditional notation on the page, but instead an instruction like “crying” or “whip sounds” and you just have to go for it and create those sounds?

Yeah, all of that. It gives the performers a chance to insert themselves a little bit. Especially with the different styles . . . When you jump into a hoedown, there’s something “off the page” about it, even though it’s on the page.

But I want to be careful when I say that because my experience with John has been quite the opposite, where it’s all on the page. There’s a seriousness with the music and with the notation, and I find that whenever people take an inappropriate liberty with it, it doesn’t work. Zorn has really refined the music on the page. Cat O’ Nine Tails and some of the other earlier quartets have these moments where it’s not notated necessarily with notes and rhythms, but there’s still a Zorn “ethos” that the performer needs to be aware of. It’s not like a free-for-all.

It sounds like he’s asking for something very specific, even though the personality of the musician is so unique.

Working with Zorn . . . he can be hard, but he’s so loving and supportive. Yet, it’s always either working or not working.

(John Zorn, photo by Scott Irvine)

In the liner notes for the new album, regarding Cat O’ Nine Tails, you write about “the virtuosity of the notes and the flow.” Can you talk about what you mean by “flow”?

It’s like what I said before about changing channels on the TV, it’s like you’re in a mode, you’re going along, and then you click the channel, and suddenly, you’re in a different mode. Finding the flow in that kind of context is hard because there’s no transition. The “jump cut” is part of the music. But it’s an unusual way of performing. With Cat O’ Nine Tails, we’re always rehearsing to get that moment to be less of a thing. That you are just here, and then there. It’s really hard for humans to do that.

What about the overall arc of a composition where there isn’t a traditional beginning, middle, and ending, but there is a trajectory and balance? Is that also something you guys need to be aware of with Zorn’s compositions?

Yeah! I think the trajectory of it speaks for itself. There are moments where things are changing rapidly, and there are other moments where you stay in one mode for a while, and those are usually heavier, slower, and more contemplative. The overall shape of Cat O’ Nine Tails is kind of, in a way, traditional. It has its whole journey, and a beautiful cadenza ending.

I also hear comedic timing in Cat O’ Nine Tails. Is that a thing too?

It’s a unique kind of comedy.

Often we’ll perform on what I call “Zorn-a-thons,” which is when Zorn takes over a concert hall or a museum for a whole afternoon with lots of different performers. He’s always there on the stage — he likes to announce all the performances — and often just sits onstage, sort of hidden somewhere right behind us. And whenever something happens that he likes or tickles him, he’ll just laugh out loud, or he’ll exclaim something like, “Fuck yeah!” That happens a lot in Cat O’ Nine Tails, but he takes it all really, really seriously. It’s not that we’re laughing at the music, it’s just sometimes the music is exciting, and we’re responding to it. But the comedy of it is more complicated. I’m not sure Zorn is trying to be funny. It’s not silly.

Speaking as a violist, and a member of JACK Quartet, has Zorn ever presented something in a score that you’ve never encountered before?

There are a lot of quintessentially Zorn things and licks that happen. His later quartets are notes and rhythms; there’s not as many requests for any kind of improvised material, and the licks are very, very unique. The way that Zorn has learned how to write for strings is really, really unique. I don’t see it in other composers’ works. There’s a voicing and a harmonic language that is so Zorn, especially on bowed string instruments. He understands what’s idiomatic and what’s not, which is so unusual, especially with virtuosic music. Every chord works, even if they’re ridiculous.

It’s physically possible to play.

Totally. It’s physically possible to play, and he’s so encouraging, I want to play it better, you know?

How does a new work by Zorn come together? I’m assuming you’re dealing only with notation. He doesn’t bring you a MIDI mock-up of the music.

Zorn usually sends us an image of the handwritten score, just to say, “Here it is!” And then shortly after, we’ll get an engraved score. The quartet will then rehearse on our own to get a sense of the scope of it. He loves to rehearse and get into the details of (the score). If we make any kind of change with him, like a note or an accent, it immediately is updated in the published score. So he is a stickler for getting the notation correct.

Does a piece come together in an additive manner, meaning, doing one section of the music at a time, no matter how short, until you get it right, before moving on to a new section?

We are a full-time quartet, and because we play together all the time, we have a general practice of being able to sit down at the first rehearsal and play through the whole piece. I find that’s helpful to do at the beginning to get a sense of the whole thing, rather than immediately breaking it down into smaller chunks.

Does the metronome come into play when rehearsing any of these pieces?

All the time. Constantly. We’re very pro-metronome in general. In a work like Remedy of Fortune, because the piece is full of so much subtlety, the little changes that happen become very significant. So, the difference between ten clicks on a metronome can really alter the vibe, and if we drift away from that, we lose something. People talk about having “perfect pitch.” We strive to have perfect bpm. (laughs)

The metronome is a creative tool for composers.

Absolutely.

(JACK Quartet, photo by Petra Hajska)

Zorn’s music is heavily inspired by other creative mediums. Has your experience with Zorn’s music led you to discover new books, films, or other types of art you weren’t familiar with before?

Almost all of Zorn’s pieces have some sort of film, literary, or mystical reference. Just hanging out while traveling, and our being backstage, there are a lot of conversations about film and literature. I’ve read some books he’s recommended. He’s got the most insane knowledge of beautiful cinema . . . He’s just a person who is curious about all art.

Does this deepen your appreciation of a piece of music you’re working on, if you become more aware of that source of inspiration?

Definitely.

On the new album, The Remedy of Fortune and The Unseen are both pieces Zorn composed specifically for JACK Quartet, correct?

Yes.

Did he compose with your respective talents and personalities in mind, much like a jazz composer will write for specific players and improvisers?

I’m not sure. Part of me thinks he’ll just write the way he writes no matter what, and he’s just searching for performers who are interested in that. But, if he’s writing with us in mind, I can’t help but think that that viola is for me. (laughs) But that’s a mysterious answer. I can’t really know what he’s thinking . . .

I definitely feel the friendship and connection. And I also think that he writes idealistically. I mean that in the best way. The music comes out of him regardless of the performer.

I’ve always thought of Zorn as a collaborator . . .

Maybe I’m thinking more of his classical music. It is all for specific people; it’s just hard to speak about specifically.

Again, in the new album’s liner notes, you write, “(Zorn) takes care of the musicians he loves. And we know he loves us because he tells us.”

Mm-hmm.

As a composer, I can honestly say that when things are going well with a musical ensemble, the feeling that I have is a kind of love for all of the musicians. That connection, or love, is that an atypical experience for you with composers?

Well, it’s kind of an atypical experience with humans. I feel like a lot of people in our society are hesitant to express their love verbally. But having a conversation with John Zorn is just so incredible. He’s so appreciative. He’ll laugh, he’ll cry, he’ll get angry; he’ll express himself in all of these human beautiful ways.

I think John Zorn stands up for himself in a way that is unusual. It’s possible people aren’t used to that. It’s an unusual way to be in our society, to stand up for yourself, but in doing so, he built a lot of trust. I trust him. And he inspires me, not just to play his music well, but to stand up for myself.

At Roulette, JACK Quartet will perform Zorn’s quartet Memento Mori, which was composed in 1992 and is dedicated to laptop and electronic musician Ikue Mori. For the performance, Mori will improvise along with the quartet’s interpretation of the piece. How is that going to work? Is Mori working from the score or directions, or is she going to do her thing while you guys play the piece?

I think that what you think it’s going to be like is probably what it’s going to be like! She is just incredible and knows John Zorn’s music so intimately. She’s a trusted collaborator. She knows what to do. I don’t want to prescribe how the performance is going to be, but it’s going to be a glorious collaboration between all six of us.

There are a lot of pieces by Zorn for improvisers and others playing notated music. This happens a lot, where a solo piece will become a chamber piece, but the soloist’s part is not composed. It’s an interesting way to fuse improvisation with composition, to have one person completely improvising, and the other person playing strictly from the score. That’s a very Zorn situation. I can’t imagine what it would be like to be chosen by Zorn to be one of those improvisers.

How does this impact your performance? Do you have to tune out the improviser? Do you get carried away and then lose your place? (laughs)

In the case of really energetic music, it ramps it up and takes it to the next level. In the case of mystical music (like Memento Mori), it transports you into a new territory. But we’ve played Memento Mori so many times just by ourselves, and we get ourselves into a mystical place. But now, it’s going to be a totally different experience.