Tierney Malone: Blindfold Test

Welcome to a new Night and Day "Blindfold Test" with visual artist, historian, and DJ, Tierney Malone.

(Tierney Malone, photo by Jehnifer Henderson.)

Welcome to the “Blindfold Test” for Night and Day with visual artist, historian, and DJ, Tierney Malone.

Originated by Downbeat magazine, a “blindfold test” is a listening test that challenges the featured artist to identify and discuss the music and musicians performing on selected recordings. No information is given to the artist in advance of the test. I will be doing more of these for Night and Day, not only with jazz musicians, but with musicians from all genres, as well as artists and writers.

Born in Los Angeles, and raised in Shipman, Mississippi, and later, Mobile, Alabama, Tierney Malone journeyed to Houston to study art at Texas Southern University and had his first show in the city in 1987. Since then, Tierney has made it his mission to celebrate the rich musical history of Houston through his paintings and murals, which draw on the typography of album covers and nightclub signage; a multimedia installation, The Jazz Church of Houston; and his popular radio show, Houston Jazz Spotlight, which airs Monday at 5 p.m. CT on KPFT HD2.

For this blindfold test, I purposely chose Houston music Tierney features on his show or references in his paintings and installations, hence the laughter that followed pretty much everything I cued up.

One more note: Anyone who has listened to Tierney on KPFT knows the deep, melodious sound of his voice, as well as the unique way he phrases and accentuates his words is impossible to recreate in a transcribed conversation.

(Scroll down for a Spotify playlist of the following tracks.)

(Lionel Hampton and Arnett Cobb, Aquarium, NYC, ca June 1946. Photograph by William P. Gottlieb.)

Arnett Cobb

“Smooth Sailing” (from Smooth Sailing, Prestige, 1960), Arnett Cobb, tenor saxophone; Buster Cooper, trombone; Austin Mitchell, organ; George Duvivier, bass; Osie Johnson, drums.

Tierney Malone: (Laughs) It’s familiar! That’s Arnett Cobb, “Smooth Sailing.” That’s the version I used to use at the start of my show, Houston Jazz Spotlight.

Chris Becker: When did you first become aware of Arnett Cobb? Was it before you came to Texas?

I got the meet Arnett Cobb in 1988 when he played with his quartet at the Contemporary Arts Museum, Houston. I was working there as a guard, and he played at an opening. I went up to him and introduced myself, and he leaned back on his stool with his crutch and said, “Nice to meet you, young man.” (Editor’s note: After a car accident in 1956, Cobb could not walk without crutches.)

I met Arnett’s daughter, Lizette, the year before. My conversations with her over the years hipped me to Arnett’s importance, and the whole landscape of Houston as a city that had a history of jazz.

Arnett Cobb was the key.

Oh, definitely. He and his daughter. No matter what stories Lizette told, her father was always the central figure. If he was working somewhere, she would tell a story about some of the sidemen he played with who she knew not as celebrities, but as the men who worked with her father. So she had a whole different worldview on these cats. They were just . . . men! (laughs) Whereas I would hear a name, and I’d be like, (whispers) “Oh, my goodness!”

That was right at the time when I was beginning to figure out what lane I was going to explore in my art. Lizette helped me to see these men not as music demigods, but as everyday cats just trying to make a living and take care of their families. I began to see them, and cats from the Negro (baseball) leagues as my contemporaries.

That was also the time of Wynton Marsalis and Spike Lee (whose 1990 film Mo’ Better Blues included music by Branford Marsalis), so there was a whole other new focus on jazz. And I was really into jazz. I was spending whole paychecks on albums! I was digging all of the time in record stores, just looking at every album they had.

(Lonnie Johnson and Victoria Spivey performing “Black Snake Blues,” 1963.)

Victoria Spivey

“Black Snake Blues” (from The Victoria Spivey Collection 1926-27, Acrobat, 2015; originally recorded for Okeh, 1926), Victoria Spivey, vocals and piano.

Bessie Smith?

Nope. Good guess. It's Houston person.

Oh, that’s Victoria Spivey!

She’s playing piano, and she starts the song by imitating the sound of a trumpet.

Her voice sounds heavier than other recordings I’ve heard. I became aware of Victoria when I heard her recording with Louis Armstrong, “How Do You Do It That Way?”

She had a revival in the 1960s. Before that, she recorded in Houston, then retreated for a period of time —

No, she didn’t retreat. She went to Chicago, brother! Chicago was the place. That’s where the energy was. That’s where Victoria was making her name. Chicago and New York. She was recording like crazy.

Victoria was in Chicago, and then comes (singer, pianist) Sippie Wallace’s whole family! So you’ve got (pianists) George and Hersal Thomas, and then George’s daughter, (singer, pianist) Hociel Thomas. All of them were performing there.

When rock and roll hit, a lot of blues singers just left the road and started doing something else. That’s when Victoria created Spivey Records (in 1961) to give these cats an opportunity to work. She’s credited for reviving Sippie Wallace’s career.

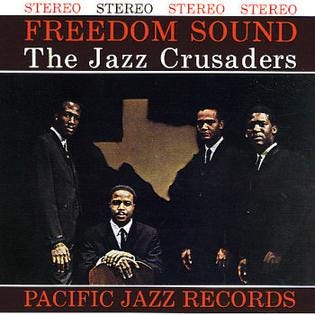

The Jazz Crusaders

“Freedom Sound” (from Freedom Sound, Pacific Jazz, 1961) Wayne Henderson, trombone; Wilton Felder, tenor saxophone; Joe Sample, piano; Roy Gaines, guitar; Jimmy Bond, bass; Stix Hooper, drums.

Oh, yeah! That is The Jazz Crusaders. It’s my bed music (for Houston Jazz Spotlight), usually when I’m talking. But I use (Houston saxophonist) Shelley Carrol’s version, with Sebastian Whittaker on the drums. Sebastian was an incredible drummer and a beautiful human being.

This is Joe Sample’s civil rights anthem. I didn’t know that until I heard an interview with (trombonist and co-founder of The Jazz Crusaders) Wayne Henderson. He said Joe wanted to get involved with the movement, but they were working at the time. Everything was happening for them right at that moment. According to the story I heard, that’s when Joe wrote “Freedom Sound.”

(Cover art designed by Loring Eutemey.)

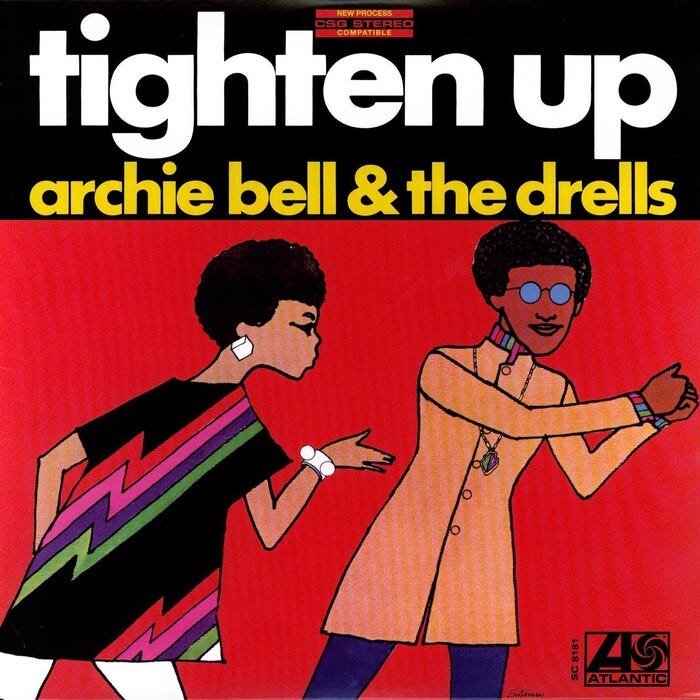

Archie Bell & the Drells

“Tighten Up” (from Tighten Up, Atlantic Records, 1968)

(laughs) I’m in Shipman, Mississippi. I’m probably four or five years old, in a room with my aunts, who were all teenagers, and whenever a song came on the radio they liked, they’d turn the radio up, and they were dancing, and I would be right in the middle of them! Hearing this was probably the first time I ever heard the word, “Houston.”

And the backing band on this is the T.S.U. Tornadoes?

Not tornadoes. Toronadoes! Oh, I’ve been checked on that!

Nelson Mills, III, a master trumpeter from Houston, is the trumpeter you hear on this. The Toronadoes were a band before Archie Bell came around. There was a promoter named Skipper Lee Frazier — you should look him up, he’s a very interesting cat — and he brought Archie Bell, who had a new dance, to hear the Toronadoes. The music for “Tighten Up” was a piece they would play at the end of their sets. But Archie Bell and the Drells got all of the credit. Nobody knew that the Toronadoes were the ones who created the music, and it left a very sour taste with brother Mills. And, of course, Skipper Lee Frazier, as it was pretty much customary in those days, was not about equity.

You talked about “Tighten Up” at your BLACK STEREO exhibit at Hogan Brown Gallery. Did this song announce Houston to 1968 America?

Brother, it put Houston on the map! It’s an iconic opening: “I’m Archie Bell of the Drells of Houston, Texas!” And that (sings the song’s recurring horn and keyboard break) – the Toronadoes take credit for creating that, but you hear it in a lot of songs during that period of time. So, you’ve already got this popular sound, and then you’ve got the soul clap, which brings a whole other level of energy to the song. These kinds of songs ask you to be involved.

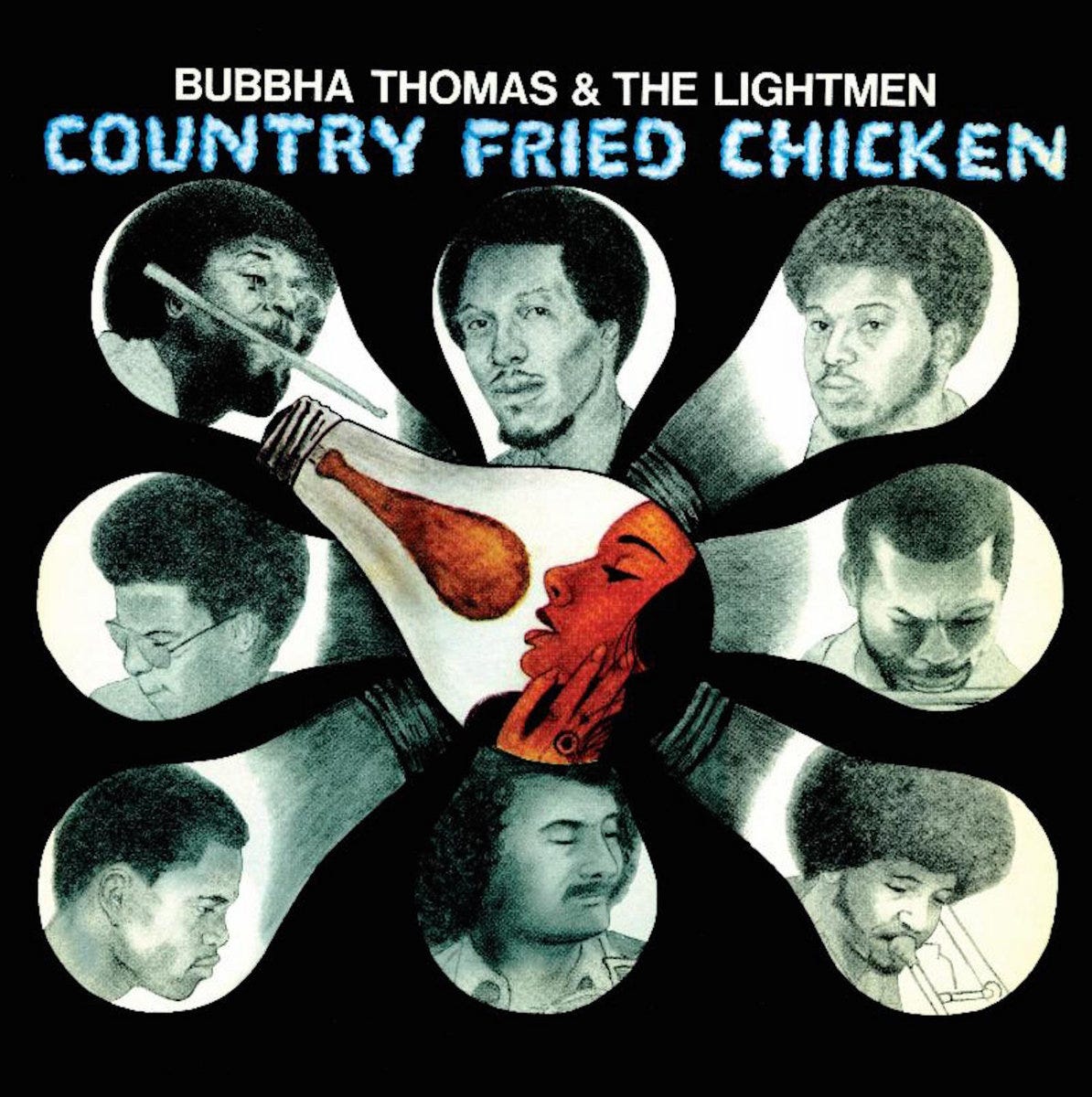

Bubbha Thomas and the Lightmen

“Country Fried Chicken” (from Country Fried Chicken, Lightin’ Records, 1975; Recorded at Nashville Sound, Houston, Texas). Bubbha Thomas, drums.

I know this . . .

It’s another Houston band.

Kashmere Stage Band?

Good guess. There is a Conrad O. Johnson connection . . .

Is it Bubbha Thomas and the Lightmen? That’s what I thought of at first!

This is from an article about Thomas: “By the late ’60s, the lights were on for Bubbha Thomas. Music had illuminated his world, but in an era in which Black Americans like he had fought for and won their civil rights, Bubbha realized he had more to say than he could manage from behind the drums.” To help bridge the gap between Houston listeners and jazz musicians, he had his own radio show and also wrote for the Houston Informer. Have you heard of that paper?

Yes. It was a small, local paper. A Black paper. But I haven’t seen it in years. Houston Informer, the Houston Forward Times, the Houston SUN, and the Houston Defender, were Black information publications.

Were these newspapers around when you came to Houston to study?

Yes. While I was at TSU, I did some illustrations and comic strips for the Houston Defender. I was hired by Sonceria Messiah-Jiles, the owner of the newspaper.

And your practice moved into Houston jazz and culture . . .

I didn’t do anything about Houston until later, (when I made) that connection between these cats who had these unconventional occupations but were having to deal with the conventions of their times, meaning, jazz musicians had to pay rent. Jazz musicians had families and had to pay bills. I was initially just basking in the product, I wasn’t thinking about the people who made the product, the product of music. What those cats had to deal with compared to what I have to deal with is . . . Negro league baseball players went from town to town and found people to play ball with. Can you imagine traveling Jim Crow rabid America, and then after you get through dealing with whatever you dealt with, once you got to the stadium, you had to play to the highest of your ability?

Lizette Cobb told me, when she heard big band music, it was never “happy” music to her. It was always angry music. But the energy served its purpose. The way she put it, the bandstand was the only place where these men could express their frustration with the world that they lived in. But at the same time, they were all striving for excellence.

Jewel Brown

Jewel Brown with Louis Armstrong. Live From The Goodyear Jazz Concert, NYC 1962.

Ah, yes! I tell people, if you want to know who Miss Brown was until the day she left this earth, this performance, that’s her personality. She pulled no punches. She’s a straight shooter. She’s not suffering any fools, and she knows her worth. All of that comes across in this performance.

I’m glad to see there’s a lot of good video documentation of and writings about Jewel Brown that people can explore.

I interviewed her on my radio show many, many times, and was fortunate enough to be considered a friend.

Love this!